Discover more from Social Studies

Back when they used to care about ideas, political leftists could be divided, crudely, into two intellectual camps: vulgar Marxists and everyone else. Orthodox Marxists were (and are) materialists, meaning, basically, that they reduced everything to economic motivations. If a country went to war, the reason could be found in how that war served the economic interests of that country’s ruling class. If a society had a generous social safety net, the explanation could be revealed by looking at the balance of power between labor and capital.

Critics of this worldview thought it overlooked all kinds of other reasons people do things that have nothing to do with economics. The first and most famous of these critics was the German sociologist Max Weber. While Marx was myopically fixated on capitalism (even his theories on feudalism were really just an origin story for the emergence of capitalist relations of production), Weber’s interests were sprawling, encompassing everything from the genesis of organized religion to the social organization of warfare.

Weber found Marx’s reduction of all of society to class struggle unhelpful to any number of questions, such as why certain religions adopted a cult of asceticism and others did not, or why political officeholding in the modern world is no longer hereditary, as it had been for centuries. Instead, he believed that different fields of human activity had different sets of motivations that were peculiar to each. Religion, he believed, emerged from the competition over the authority to define truth. Politics, he argued, was the realm of struggle over the power to dominate others. People didn’t pursue these ends merely as instruments to consolidate the economic power of their social class, as Marx assumed. They pursued them for their own sake.

This was all very academic back in the nineteenth century, when Marx and Weber were formulating these thoughts. But during the Cold War, decades after their deaths, the consequences of this schism were all too real. The part of the socialist left that remained loyal to the Soviet Union even as Stalin’s atrocities became incontrovertible was the part that was most committed to the idea that no other power motivates human behavior but class power. That conceit made it easier to believe that Stalin’s totalitarian regime was nothing more than Marx’s “dictatorship of the proletariat,” which would “wither away” as soon as the capitalist class was defeated and true communism was achieved.

Those who saw things in the way that Weber did, on the contrary, recognized that the state bureaucracy generates its own incentives, entirely separate from the class struggle around it. Political actors covet not the theoretical power they derive indirectly through their social class’ control of the means of production, but the specific power that they can see with their eyes and touch with their fingers: the power the state grants them personally through its laws and offices and titles. And this being the case, there was no reason to believe that the Soviet state tyranny would just spontaneously dissolve itself. The state bureaucracy had become a social class in itself. It was a permanent organ of the social structure.

Robert Michels, an Italian socialist intellectual, understood this tendency and codified it as the “Iron Law of Oligarchy.” Michels believed that as organizations become bureaucratized, they begin to take on their own institutional interests, which are divorced from those of the constituents they purport to serve. The people who staff those organizations begin to align themselves not with the interests of the constituents they represent, but with those of the professional organization instead. A socialist party begins as the organized voice of the working class, aligned in every way with its interests, but eventually what serves the party’s electoral and fundraising ambitions begins to diverge from what’s necessarily best for workers. Soon party officials accommodate themselves to an agenda that serves the party even if it screws workers, while continuing to pretend to speak on behalf of the working class. This more or less describes what the Democratic Party has been for a couple generations now.

Today’s left has either entirely forgotten this lesson or willfully ignores it. As it has become increasingly alienated from the working class and dominated by the credentialed professional managerial class, the left has adopted the latter group’s idolatry of professional institutions. You can see it in its doe-eyed reverence for the non-profit industrial complex. You can see it in its contempt for those who question the pronouncements of experts. You can see it in its prudish obsession with following the rules.

The city of San Francisco has a budget of over a billion dollars for homelessness. It spends more than $60,000 per tent per year on its homeless encampments. Where does all that money go? It goes to the city’s myriad contractors: Urban Alchemy, Glide Memorial Church, housing developers, “wraparound” service providers, etc.

The people who work for these organizations are not corrupt. They don’t sit around in staff meetings brainstorming new ways to scam the city. But they do have payrolls to meet and office rents to pay. They have metrics to hit to show their donors that their services are not just helping, but serving more and more people each fiscal quarter. Like most organizations, they measure their success in growth, not contraction.

All of these mundane operational imperatives add up to an insidious disincentive to solve the problem that these organizations exist, on paper, to solve. It’s hard to justify expanding your services and increasing your budget when the population that you’re serving is getting smaller. So the incentives align to favor approaches that perpetuate rather than eliminate homelessness and drug addiction.

Thus, rather than pursue policies that break people’s drug dependencies, the homelessness services and advocacy industry champions an approach that manages addiction: needle exchanges, safe consumption sites, and other “harm reduction” strategies. Rather than find ways to put people into shelters, the non-profit industry advocates for people’s “right” to be able to pitch a tent on the streets, making the problem ever more visible to residents, who in turn vote to shovel yet more money toward those very organizations.

The approach is so transparently self-serving and so obviously unhelpful to drug-addicted homeless people that even the homeless themselves think it’s ridiculous. “If you’re gonna be homeless, it’s pretty fucking easy here,” one street addict told Michael Shellenberger. “I mean if you’re gonna be realistic, they pay people to be homeless here.”

“The level of freedom you get” to be homeless and do drugs “is hard to compare to,” another said. “If you were anywhere else in the country doing what you're doing here, like, your ass would be under the jail for years and years.”

The homeless service and advocacy non-profits are the reason it's like that in San Francisco. It serves their organizational interests.

Katie Herzog has pointed to a much different example of how organizations seeking to sustain themselves can manufacture the existence of social problems rather than the other way around. There’s a reason, she argues, why the issue of trans rights suddenly became ubiquitous in such wild disproportion to the tiny representation of trans people in the population. The reason was that we had achieved marriage equality for gays and lesbians. Once the vast and well-endowed national network of LGBTQ groups in the United States achieved this historic victory, there wasn’t much left for them to do in the struggle for gay acceptance and equality; they had won.

Those powerful lobbies could have just closed up shop, but that’s not in the nature of established organizations, which is to sustain and grow. So instead, they pivoted to a new crusade: trans acceptance. The new mission is noble beyond question, but the degree to which it has dominated American politics over so many other issues, and the level of hyperbole (“trans genocide”) it inspires, points to a certain level of grade inflation, and that grade inflation serves an interest. The moral panic that advocacy groups and the media have generated around anti-trans bigotry has given a second life to the erstwhile, nearly defunct LGBTQ movement, whose updated name reflects its rapid expansion: LGBTQ2SIA+.

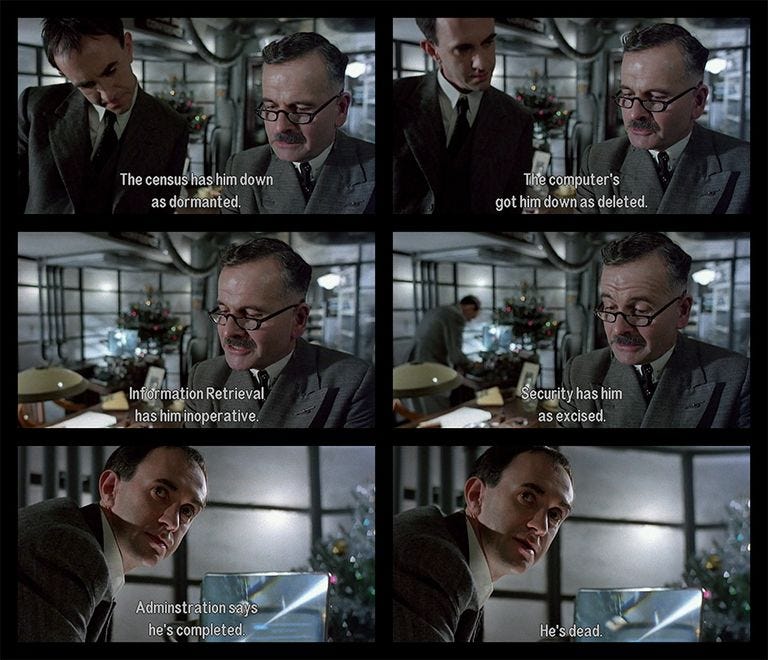

The most obvious example of all of the Iron Law of Oligarchy is the one that’s most instructive for the near future: the War on Terror. One can argue whether the powers the government appropriated for itself after 9/11 were ever anything but cynical to begin with, but it’s self-evident that, once established, the state’s new authority wasn’t going anywhere, no matter what happened to the terrorist threat that had provided its original pretext. More than 20 years after a failed attempt to take down a transatlantic flight with a shoe bomb, we’re still removing our footwear at TSA checkpoints, and more than two decades after passage of the PATRIOT Act, as we learned from Edward Snowden, the surveillance state has ballooned into something out of the fever dreams of a conspiracy-minded paranoiac.

Today, in the midst of the slow-motion 9/11 that is Covid-19, we’re living under a state regime that few of us ever thought possible: one that micromanages our most banal behaviors in public, that promulgates new rules almost arbitrarily, and that enforces them, at least in states like mine, by enlisting us to spy and shame and tattle tale on one another. You can make the case, as people do all the time, that wearing a mask indoors is no big deal, that getting a vaccine is a tiny sacrifice to make, and that showing your proof of vaccination is a trivial price to pay to save countless lives. I could dispute the efficacy of each of those dictates on empirical grounds, but the larger point is a cultural one: in little and not-so-little ways, the last two years have taught us to revere obedience and to vilify dissent. For many on the Left, censorship by corporations has become not only permissible, but obligatory. There’s no reason to believe the threat to free speech will end there; the Biden administration is already testing our tolerance for state censorship. The state has been gifted these newly accepted techniques of social control, and this newly pervasive public will to comply. Does anyone really think politicians and the administrative class is just going to give up these powers?

Liberals who have been applauding this consolidation of power within the administrative state either fail to appreciate these dynamics, or are grateful for them since it’s their team that’s currently in charge. But they should be careful what they wish for, and consider the potentially disastrous unintended consequences of these kinds of transformations.

In fact, if the lab leak hypothesis proves to be true, then a version of the Iron Law of Oligarchy is the reason we got stuck with a global pandemic in the first place. “Gain-of-function” research was originally funded after 9/11 so that government scientists could stay one step ahead of terrorists who might modify a natural virus and turn it into a bioweapon. Between 2001 and 2003, Anthony Fauci’s annual anti-terror budget at NIAID went from $53 million to $1.7 billion. Then, as the shock of 9/11 faded, the urgent rationale for carrying on this dangerous research faded along with it. But if there’s a rule of political thermodynamics in Washington, DC, it’s this: once you fund a program, it becomes quite hard to un-fund it. That’s because, like the homelessness industrial complex in San Francisco, those programs take on their own institutional interests, with entrenched stakeholders who will fight to keep the funds rolling. The federal money going into gain-of-function research kept labs open, grants funded and scientists paid. Fauci wasn’t about to just let Congress shut it down, when he could simply shift the justification for that funding. Soon enough, it wasn’t terrorists, but Mother Nature who threatened the world with naturally emerging superbugs. The appropriations kept passing, the funds kept flowing, and the research continued, until someone, perhaps, broke a beaker and started the Covid-19 global pandemic.

Since we can’t predict the future, we can only guide our actions through the vague patterns we perceive in politics over time. We’ve seen this one at every stage of history, from the evolution of the Catholic Church to the origins of the pandemic. By tilting the balance of power between the state and the public in favor of the former as we have over the last two years, we may have repeated that mistake yet again. As the pandemic recedes, this new architecture of authority may be put to new uses, in the name of new emergencies. And we will be conditioned to comply.

Subscribe to Social Studies

Politics, media and social theory

Thank you for another wonderful article. I think the problem with this country (and perhaps all of them) is that we never understand that the people in charge are just like the people around us. Yeah, there are some great and altruistic ones that you could hand a million dollars to, ask them to watch it, come back a week later, and it would still be sitting there. Some people are self-aware and understand that they are not helping, for example, the homeless by giving them tents, even if their jobs depend on it. They have conviction and purpose and would rather find real solutions, no matter whom they have to involve to do it and what they have to give up. And then there's the other 75%. (I made that number up. I have no idea. Sometimes it feels like closer to 99%.)

I know acknowledgment of a problem is the first step to fixing it, but we've dug ourselves a deep, deep hole here, and I'd love to read an article about solutions. For example, I have noticed a problem with "scale": Scale of the federal government, scale of our corporations, scale of our non-profits, scale of our media, scale of our parties. We have a serious crisis of scale. That might be a place to start. We stand no chance until we cut organizations, entities, and institutions down to size.

Really nice synthesis; thank you.