Magic Words

Stop apologizing.

Last week, the American Booksellers Association sent out a letter to its members that became an instant classic in its literary genre, the Groveling Public Apology. “This week we did horrific harm,” the first sentence began. “Last week, we did terrible and racist harm,” the second sentence opened. The ABA “traumatized and endangered” people; it “erased” and “marginalized.” It perpetrated “egregious, harmful acts that caused violence and pain.” The ABA’s actions were “negligent, irresponsible, and racist,” not to mention “negligent, irresponsible and transphobic” (their repetition, not mine).

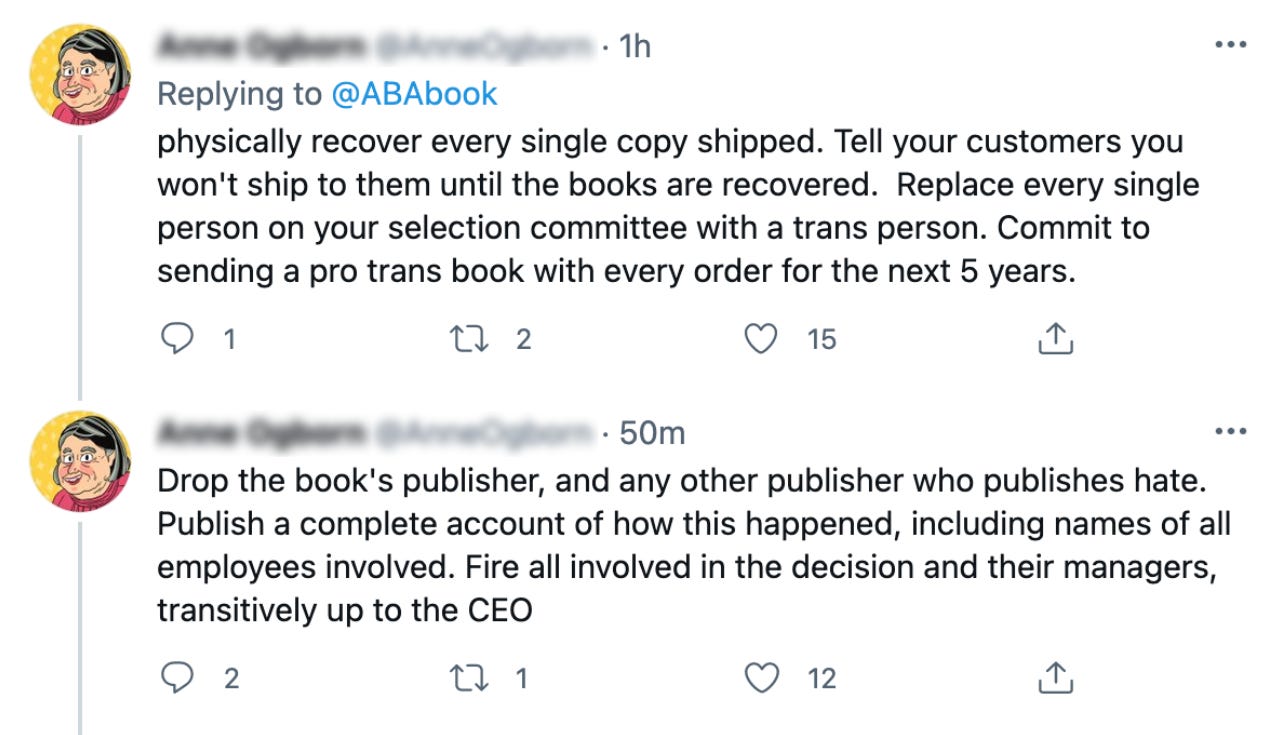

A year ago, I might have snarked that one would think from this apology that the ABA had perpetrated a hate crime. But by now it’s too obvious a joke to be amusing. I’m sure you can already guess what the scale of the offense was. It will shock no one that an apology this histrionic was occasioned by the snafu of mailing out a problematic (in this case, allegedly transphobic) book to member bookstores for promotional purposes, and the further accident of using the wrong cover image (of a book by the same title written by a right-winger) to market a book by black authors. The ABA made an error in judgment, at worst, and a careless mistake. For this the institution was compelled to beg forgiveness for acts of racist and transphobic “violence.”

It’s absurd, but it’s also hackneyed. These episodes of woke ritual self-abnegation are so ordinary they’re barely worth gawking at anymore. But they’re also so frequent that it’s worth asking why. Whose interests do they serve? What fuels this idiotic cycle of scenery-chewing melodrama? What is this trajectory we’re on and where is it leading us?

An apology is unlike other statements. Most statements are declarations about the world or about certain circumstances within it. “It’s hot outside” or “I’m mad at you” are two such statements. They assert that a certain state of affairs objectively exists.

An apology is different, and more complicated. It may seem similar at first. If you equate “I’m sorry” to “I feel badly about what I just did,” then an apology is just as straightforward a descriptive statement as “I’m mad at you.” But that’s not actually what “I’m sorry” means.

You can tell that’s not what it means because we don’t actually require someone to feel badly in order to accept their apology as a true statement. Sometimes we couldn’t care less how they feel about what they did. For instance, if someone gives you the wrong information and then corrects themselves, they might reflexively say “I’m sorry,” such as in this exchange:

“Excuse me, what time does the bus arrive?”

“2:45.”

“Wait, but it’s only 1:30. The next bus doesn’t arrive for an hour and fifteen minutes?”

“Oh, I’m sorry. I meant 1:45.”

Do you think the person who answered “2:45” at first actually feels terribly about their mistake? Probably not. If that feeling doesn’t exist, does it make their statement “I’m sorry” a lie? Not in the slightest. Does the other person even care if they feel badly or not? The thought probably never even crossed their mind.

Another example is a coerced apology. If a company did something wrong, they might be sued. The company might then agree to issue a public apology. They might do this for purely self-interested reasons, such as to avoid a trial, or a large monetary settlement, or the continuance of litigation. Would anyone actually believe in a case such as this that the company’s executives felt sincere remorse, and so were moved to apologize? Almost certainly not. Would it matter to anyone that this was not the case? Probably not. The value of the apology has nothing to do with the emotional state of the company’s leaders. Its value lies elsewhere.

The sociologist Erving Goffman saw the apology as an acknowledgement to the public that the moral rules are a certain way, and as a request to be deemed to stand in the proper relationship to them. It’s an entreaty to others to correct a projection of oneself that has been thrown off balance by an action one took that contradicts that projection.

Goffman understood “the self” to be a 24/7, continuous public performance. In our interactions with one another, moment by moment, we’re constantly playing roles: the good student, the attentive father, the diligent worker, et cetera. We play these roles even — perhaps especially — to ourselves, whether or not anyone is there to see us.

By this Goffman didn’t mean to imply that these roles are somehow inauthentic. He didn’t believe there was some metaphysical “real” self that lay beneath our outward presentations. If your behavior is consistent with what you claim to be, that’s who you are — your “authentic” self. It’s only when your behavior is at odds with that presentation that the question of fraud arises.

Typically, people take it at face value that the way you act in front of them is consistent with the way you behave most of the time. As long as everyone is in agreement about this, who you “really” are is quite straightforward: it’s who you present yourself as. (Goffman was particularly interested in what he called “total institutions” — jails, asylums, etc. — because these are settings built specifically to deny that the person you project to the world is who you “really” are.)

The apology is the fix for when this system breaks down — for when you have presented yourself to the public as one thing, but your behavior has indicated that you are another. The apology is how you repair this disjuncture.

Goffman described the act of apologizing as “a gesture through which an individual splits himself into two parts, the part that is guilty of an offense and the part that disassociates itself from the delict and affirms a belief in the offended rule.” When you apologize, in Goffman’s view, you become a sort of Shrodinger’s Cat. On the one hand, you’re the person who everyone objectively knows committed the misdeed you’re apologizing for. On the other hand, you’re also the type of person who knows better than that, who would never do such a thing, who shares in the disdain the aggrieved have for your misconduct. You are both of these people at once — a cat who is in the box and, yet, not.

By splitting yourself in two, you are allowed to offer up one projection of yourself — the one that did the misdeed — as a sort of sacrificial lamb. If the apology is accepted (and the acceptance is sincere), this flawed version of yourself is deleted from your permanent record, and your other self, the one that would never think to do such a thing, is welcomed back into polite society intact. Your self is made whole again, in harmony with the person you present yourself to be.

This is not just a relief to you; it’s also a public service. When you apologize, you do two things. First, you provide restitution of a sort to your “victims,” by conceding that you were in the wrong and that you’re well aware of it. In most cases, this symbolic restitution is enough. If the offense is more serious, or if it involves material loss, then apologizing might not be sufficient; one could reasonably expect you to take measures to restore to your victims what was lost, as well. If your offense had cost them money, you might need to pay them back. If it had cost them reputational harm, you might need to speak publicly on their behalf to clear their names.

More typically, though, the offense is small and largely symbolic — bumping into someone at the grocery store, or talking over them in a conversation. As Goffman observed, in those situations both parties are usually more concerned with just getting things back to normal so everyone can move along with their lives. The apology is, in Goffman’s terminology, “remedial.” A minor transgression has been committed. Things are, for a fleeting moment, in a moral disequilibrium. This is not a trivial problem, even if the offense is frivolous. If the state of imbalance is not corrected, things can get ugly, quickly: consider how, in seconds, cutting someone off on the freeway — the vehicular equivalent of bumping into someone in the grocery store — can escalate into full blown road rage. Fortunately, in the typical instance, the perpetrator apologizes, and everything is set right again. The flow of daily life has been restored. We can forget about it and get on with more important things.

The second thing you do when you apologize is uphold the moral order. When you do something “wrong,” whether it’s a moral transgression or a mere violation of etiquette, you’ve aggrieved not only the persons you directly impacted, but also, symbolically, all of society. Your act is not merely a private affair. It’s everyone’s business, because everyone has a stake in everyone else submitting to a universal moral code. This is one reason why, in criminal court, cases are called things like “The People of the State of California v. James Robinson, Jr.” or “United States v. Hidalgo,” rather than just one private party versus another, as it is in civil court. It’s not just between you and your victim’s family when you murder somebody. Your crime violates not only your direct victims but the entire society. You need to make amends to all.

To say you’re sorry is to affirm to the world that you recognize the legitimacy of the norm you violated. If you just spilled a drink on someone, apologizing is the equivalent of saying, “In spite of what you just witnessed me doing, I’m not actually the kind of person who thinks it’s ok to pour drinks on people. Like a normal, mentally healthy adult, I recognize that this kind of behavior is rude.” If you just, to your eternal horror, inadvertently microaggressed against someone, to beg for their forgiveness is to plead, “Please accept me as the kind of person who recognizes that complimenting you on your English is racist, and not the kind of ignorant troglodyte who would suspect you’re being overly sensitive.”

You are, in effect, bending the knee to the moral order. This is why, for moral offenses, it’s often not good enough just to apologize privately. You have to do it out in the open, in front of your friends and family, or in front of a bevy of cameras and microphones, or in front of your webcam, uploaded to YouTube. Conversely, it’s why, when you feel that the laws, rules or norms you ran afoul of are in fact morally illegitimate — say, in the case of a civil disobedience — whether you plead guilty or not takes on such significance. You might reject a plea deal that costs you only a single dollar, because you’re aware that to admit guilt is to concede that you accept the legitimacy of the rule you violated, and the entire point of your action was to show the world that the rule, or the authority that stood behind it, was unjust.

Those are exceptional cases, though. Generally, if you transgress norms, you have an interest in restoring the equilibrium of the social interaction you’re in, and affirming to others that you’re a well-socialized person who respects the moral order. This is the behavior of a normal human being.

But what happens when the other party has no interest in restoring equilibrium, and actually benefits from its rupture? And what happens if, further, the other party has an active interest in refusing to grant you the recognition of being a respectable person with a healthy regard for the prevailing morality? What if the other party is acting entirely in bad faith?

Goffman wrote the above-quoted description of the apology in 1971, when social interactions were done primarily face-to-face, or at least voice-to-voice, over the telephone. They were also typically one-on-one, or in small group settings.

Today, this interaction order is no longer the prevalent one. On social media, our interactions are virtual, highly public, and often conducted with a large number of people we do not know — even anonymous people. This has had a radically distorting effect on the social protocols Goffman wrote about.

One of the most significant changes is that on Twitter and Facebook and Instagram, there is no shared interest between everyone involved in an interaction in restoring equilibrium when a norm has been violated. As Goffman pointed out, in an ordinary, face-to-face conversation, the shared motivation to get things back to normal again after a transgression has occurred is so strong that often those who did not commit the faux pas will repair things on behalf of the transgressor, rather than wait for him to speak on his own behalf. “You’re so funny,” one might say with a forced laugh, trying transparently to pass off someone else’s rude comment as a joke. “She just joined last week,” someone might say in a chat between country club members, excusing a tone-deaf comment as one born of unsophistication, not malice.

Online, that incentive simply doesn’t exist. Granted, a rough approximation of it may persist when a dialogue on Facebook is strictly between close friends or family members, because there’s a social cost to be paid for an unresolved conflict; nobody wants this spat hanging over next week’s poker night, or next Thanksgiving dinner. But more often, that Facebook thread includes not just friends but also mere acquaintances and total strangers. There is no real social cost to be paid in that case for failing to reconcile with people, not even the fleeting unpleasantness of social awkwardness you’d all be forced to suffer through together if the transgression had occurred in a conversation you’d just struck up with strangers in person, say, at a cocktail party. The immediacy of physical proximity is lacking, for one thing, and for another, you can always just walk away from your computer or tab away from that page in your browser when a conversation hits a rough patch. You don’t even have to make up an excuse about needing to use the bathroom.

The other big difference between the online and the offline worlds is that on social media, the incentive structure is such that people benefit from conflict in a way that has no analogue in a face-to-face context. Try “dunking” on people you’re in a conversation with at a party. You’re unlikely to find people gathering behind you, patting you on the back and applauding you like you’re in a freestyle rap battle. But on social media, that’s exactly what they’ll do. The kind of antics that would make you look like a borderline psychopath at a restaurant, a bar, or in someone’s living room make you look like a hero on Twitter.

Thus, online there is a negative incentive to allowing people to split themselves, à la Goffman, and then affirming for them that the projected, contrite version of themself is the “real” version, while deleting from collective memory the version that perpetrated the offense. Not only do you score a personal victory over them by forcing them to apologize profusely in the social death match that is Twitter, but insofar as their apology serves to validate the legitimacy of the norm they violated, they’re actually assisting you in building your new moral order. There’s no reason to let them off the hook.

An apology is a kind of magic word, in that its utterance does not merely exonerate you, it actually helps to construct the social world around us. If every time you say “I’m sorry,” you’re saying, in effect, “Please accept me as the kind of person who recognizes that the norm I just violated is legitimate,” you can see how helpful that would be when you’ve just invented a new norm and are trying to bake it into our shared social reality. It’s like inventing a new religion and having people line up to pledge fealty to the god whose name you just made up.

Today, on the political left, we’re making up new norms all the time: calling people “Latinx,” announcing our pronouns, capitalizing “Black.” A year or two ago, none of us had ever heard of “deadnaming.” Today it’s the digital equivalent of pissing on someone’s grave. You can already see which norms are in the process of cohering today, in real time: erasing any metaphorical references to physical or mental disabilities (“lame,” “crazy,” etc.) from our vocabularies; acknowledging “stolen lands” before every meeting; recognizing people’s declared mental disorders as identity markers conferring upon them special accommodations and sympathies; narrowing our definition of consent to sex to exclude adults who are significantly younger than their partners, or who are employed in a less powerful position within the same industry, or who belong to an identity category purportedly lower on the power continuum.

Every time someone is compelled to apologize for violating such a norm, that norm is soldered more firmly into the structure of our collective consciousness as an accepted part of the new moral order. A year ago, almost nobody capitalized “black” in reference to “Black people.” Today, it’s part of the style guide of most major news outlets. In a year, you’ll probably be called a racist if you don’t do it in your personal communications. Each one of those steps was and will be accompanied by countless call-outs and apologies.

The reaction to the American Book Association’s apology was entirely predictable. Even though it’s hard to conceive of a more obsequious statement, it still wasn’t enough for some. And why would it be? Groveling pays dividends. The more submissive the apology, the more forcefully it attests to the authority of the rule it submits to. For champions of that new rule, there is nothing to be lost and everything to be gained from making the conditions for acceptance of an apology impossible to meet. Doing so ratchets ever downwards the depths to which transgressors must sink to survive their day of judgment, elevating the authority of the aggrieved in equal proportion.

If that sounds hyperbolic, consider what, in this case, was achieved. A trade association for booksellers equated the promotion of certain books with violence. This is baby steps from an art museum declaring pieces in its own collection as dangers to public morality, a university condemning free inquiry as a tool of potential ethnic cleansing, or a newspaper redacting its own stories to protect its readers from information that might alarm them, offend them, or prejudice their views. These are all examples I offer as part of a picture of a dystopian future, but I have no doubt that there are plenty of activists today who would look at each and wonder, “What’s the problem with that?”

The path we’re tumbling down is slippery and steep, and we’ve already picked up momentum. There’s only one way to break our fall. Fortunately, it’s easy and straightforward: Stop apologizing.

I’m glad you addressed this. This kind of behavior is what stopped me in my tracks in my own Great Awokening.

Did you watch game of thrones? these apologies are like when the up-and-coming religious order turned on one of their own, cut off her hair, made her strip naked and walk through the streets while a nun followed her shouting SHAME! And then she was allowed back into the fold.

I think the baby seeds of this were when microaggressions became synonymous with violence and trigger warnings became the norm. I understand and empathize with the desire to be thoughtful, and a general trigger warning about explicit and upsetting material is certainly not necessarily out of line, but who decides what material is explicit and upsetting? An online mob, is what you’re saying.

At some point how much do we need to apologize vs. how much does the offended party need therapy?

Some of the more radical factions in social justice —which are gaining ground —would imply or outright state that there’s nothing a white person can do to escape our awfulness. This kind of “you’re rotten to your core and nothing you could ever do can save you” is what led me right out of religion after 30+ years of being raised in one. Not about to go down that road again.

Great analysis. Goffman really helps clarify the relationship between a sort of social contract and apologies, and how demanding an apology is really demanding that someone pay respect to a particular value system.