Discover more from Social Studies

This is an ICYMI post of an article I wrote for Tablet about a week and a half ago (thus the now-outdated “last week” in the first sentence). Hope you enjoy it. I’ll try to gather some post-election thoughts for next week, after I read and process all the hot takes. By the way, the one that stands out to me so far is by the always-intriguing Niccolo Soldo at Fisted By Foucault (subscribe!).

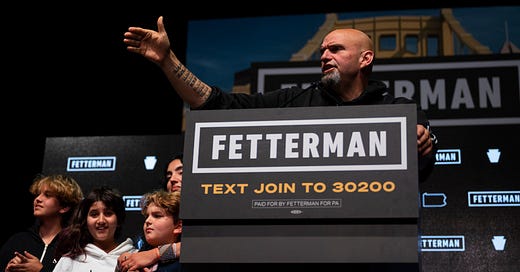

On the debate stage last week, Pennsylvania Democratic Senate candidate John Fetterman performed like one might expect from someone who survived a stroke only five months ago. In the aftermath of the debate, Democratic strategists have been asking—anonymously, of course—how anybody thought it was a good idea to foist Fetterman onto such a public stage. The simplest answer is that they thought they could get away with it because they believed their own hype.

A swarm of liberal political pundits and journalists had spent the previous weeks denouncing any questions about Fetterman’s health as illegitimate, while attacking the few reporters who dared raise such questions as heartless bigots and right-wing shills. In the process, they unintentionally revealed something essential about how the elite media distorts the public’s understanding of key issues by bullying journalists into repeating obvious lies.

Case in point: NBC News’ Dasha Burns. On Oct. 7, Burns conducted an on-camera interview with Fetterman. Because Fetterman has “auditory processing issues” as a result of the stroke, according to his campaign, he had to use a closed-captioning system to understand Burns’ questions. After the interview aired, Burns told NBC’s Lester Holt on air that Fetterman didn’t appear to understand her pre-interview banter. Burns was just doing her job by reporting on the fitness of a public official, but her assessment also seemed to lend credibility to the line of attack coming from Fetterman’s Republican opponent, Mehmet Oz, who has claimed that Fetterman is suffering from cognitive decline and covering it up. Simply for stating the facts as she had observed them, Burns was seen to be supporting the “wrong” candidate.

The media felt a great disturbance in the Force. On Twitter, blue-check journalists jumped in to defend Fetterman and throw shade at Burns. Soon, Burns’ tweets were inundated by thousands of haters calling her “disgraceful,” “trash,” and, again and again, “ableist.” The Associated Press published a syndicated story amplifying the criticism and suggesting that Burns’ remarks had given ammunition to the Republicans. The New York Times published an op-ed deploring her remarks. Savannah Guthrie confronted Burns about it on air. On The View, Sunny Hostin implied Burns had acted unethically. BuzzFeed published an article essentially accusing Burns of putting disabled people at risk of violence. Recaps of the criticisms surrounding Burns’ interview appeared in The Washington Post, LA Times and other publications where they served to legitimate the idea of a controversy that the media itself had created.

That’s how it remained for two weeks: with Burns scolded and swarmed, and other journalists left to internalize the message about what would happen to them if they too stepped out of line.

Then, Fetterman’s abysmal debate performance vindicated her. Most of us know better than to expect the media establishment to pause for even a fleeting moment of introspection but, still, it’s incredible to see how many pundits and blue-check experts chose to double down on the “ableist” defense. The few nonconservative commentators who had the gall to note the reality about the debate were promptly disciplined. “There is no amount of empathy for and understanding about Fetterman’s health and recovery that changes the fact that this is absolutely painful to watch,” tweeted New York Magazine’s Olivia Nuzzi. In response, Nuzzi was instantly accused of “ableism,” racism, acting out of hatred, and lacking a conscience. The experts had spoken! But for the rest of us, it’s an excellent time to take stock of what Burns’ colossal ratio and the subsequent swarm on Nuzzi were meant to accomplish.

When I was in college, like any budding leftist, I read a lot of Noam Chomsky. Chomsky’s most famous book is Manufacturing Consent, in which he argues that the big corporations that pay for the advertising that keeps the media industry afloat exercise a soft power over journalists. It’s not that they tell publishers and broadcasters what they can and cannot print. They don’t need to. Their looming presence as the industry’s paymasters is enough for editors and reporters to figure out quickly where the lines are that they cannot cross. Simply by observing what kind of reporting is incentivized in the business and which kinds of stories will help them get ahead in their own careers, individual journalists self-censor. What emerges is a pliant, self-policing, corporate-friendly media.

Chomsky’s theory, if it was ever true, seemed to become obsolete with the invention of the internet. Before the internet, the mass media was the only way for advertisers to reach millions of people at a time. Today, not only has social media broken that monopoly, but digital ads can be targeted in a way they never could on TV or in newspapers and magazines. No longer do corporations have to pay a surcharge on their ad spending to cover the salaries of journalists and editors and typesetters. They get a much better service for way cheaper on Google and Facebook.

In his book Postjournalism and the Death of Newspapers, Andrey Mir describes what happened next. Starved of ad revenues, print media outlets changed their business models. They had already been drifting toward partisanship, but now they saw there was money in it. Instead of seeing their readers as consumers of the ads they sold, they started looking at them as potential donors. They began appealing to their political consciences, asking readers to subsidize their noble journalistic missions, NPR pledge-drive style. “Support our brave truth-telling work,” went the pitch, “for Democracy Dies In Darkness!”

This shift went full throttle during the Trump years, as the president attacked reporters as “the enemy of the people,” instantly transforming them into heroes in the eyes of Democrats. The only way to defeat Trump and his lies, liberals came to believe, was by forking over their money to The New York Times. Only The New York Times (and The Washington Post, and The Guardian, and The New Republic, and The Intercept, etc.) had the reporting chops, the prestige, and the national audience to counter Trump’s propaganda with the truth. By subscribing to the Times, you weren’t just paying to access a consumer product; you were donating to a cause. You were doing your part to make sure the truth got pushed out into the discourse, that it reached millions of Americans who, without it, might be left brainwashed by the MAGA hate machine and its “disinformation.”

In other words, you were paying to build your own propaganda apparatus to counter Trump’s.

Under Trump, the media brands behind the news Americans consumed became badges of political affiliation, even more than they were before. If you despised the administration, you would never dream of watching Fox News. Instead, you would watch CNN or MSNBC voraciously, and share stories from The New York Times or The Washington Post on your Facebook feed. During the Trump administration this became the media’s new value proposition to its consumers, and for a select few outlets, it was a godsend. The New York Times’ subscriber rolls ballooned, as did its newsroom, becoming the largest in the paper’s history.

As news organizations became more partisan than ever before, their loyal readers and viewers came to demand a standard of ideological fealty from their coverage.

Before the internet, a politically unpopular story might trigger a flood of nasty letters to the editor, but as long as it didn’t upset any major advertisers, the haters could be safely ignored. Now that it was the readers paying the rent, things were different. A revolt by your readers, if you were a newspaper publisher post-2016, was a direct threat to your bottom line.

But there was a threat even more perilous than that: a revolt by all the young reporters you hired to cater to the millions of outraged new subscribers you had enlisted in the fight against MAGA authoritarianism. Those young reporters were true believers. They’d never known the old, aspirationally nonpartisan mode of journalism. They had joined your outlet to fight for social justice, wielding their pens as swords. So had all the app coders you had enticed away from their overpaid but unfulfilling Facebook jobs with the promise that here, you might take a pay cut but you could also change the world.

Today, a politically unpopular article or personality can leave a publisher besieged from the outside while facing a revolt from within. We’ve seen this play out again and again, especially at The New York Times. There was The Nazi Next Door scandal, the Donald McNeil fiasco, the Tom Cotton op-ed outrage, the Andy Mills brouhaha, the Alison Roman inanity and everything that Bari Weiss ever wrote or tweeted. Some of these tempests may have started with readers, others with journalists, but mostly it was hard to say, because they emerged from the swamp where the media industry’s most indignant consumers and its loudest employees coalesce: Twitter.

As these changes took place across the digital media industry, Twitter became a disciplinary tool for the journalistic profession. It became the means by which the partisan and ideological vanguardists huddled inside the media’s fortress walls could find their ragtag armies on the outside and wage war together against disfavored colleagues like Weiss and McNeil.

That’s what happened to Dasha Burns. I don’t know Burns and she didn’t respond to my request for comment. But I do know that she’s a human being. As such, I suspect that, if not for being so publicly vindicated by Fetterman’s debate performance, she may have begun to think twice before again giving voice to an obvious but unpopular truth that could draw the collective wrath of her colleagues. She may have learned, in other words, how to lie.

Instead, though, the script was changed: The real world punched through the narrative, revealing the flimsiness of the media establishment’s partisan indignation. As Fetterman stammered through response after response, the obvious became even more so: Dasha Burns was right, and all her haters were disingenuous hacks.

So maybe this story will have a different outcome. Maybe the media will experience, just for a moment, an unfamiliar feeling—humility. But I doubt it.

Fox News cracked the formula that extreme partisanship would lead to higher revenue. And it worked, and now almost all news networks have a partisan slant. People don’t want to hear the news, they want to hear their thoughts being validated by the news.

I'm sure Dasha Burns has learned to never do it again anyway. She'll be lucky to make it to any Christmas parties this year.

There's been carrying the water for the correct side since the invention of writing. It wasn't in HS I learned that Shakespeare was just the most eloquent genius patronage could buy. I had to learn that from reading, of all things, a mystery novel examining the slandering of Richard III.

We're in the currently modern world but human nature doesn't change and there's nothing more to life than power and resources and who has 'em and who doles 'em out as patronage.