When I was an undergrad, I took a class that I didn’t do very well in but that taught me a lot about detecting bullshit. The class was called “Wittgenstein and the Philosophy of Language.” The takeaway was that thousands of years of intellectual pondering about deep metaphysical questions were actually just people playing word games without realizing it.

One of the concepts we discussed in the class was that of a “necessary truth.” In philosophy, a necessary truth is just what it sounds like: it’s a statement that necessarily must be true.

“2+2=4” is such a statement. 2+2=4 must be true. It is not an empirical question. There is no amount of evidence that can prove that 2+2 actually equals 5. Spend your entire life scouring the world for that evidence and you won’t find a shred. It’s literally impossible, because we would never allow the statement 2+2=4 to be falsified. It’s simply against the rules.

Imagine one day you took two apples and added them to another two apples and ended up with five apples. Perplexed, you tried it again, and then again, and again, and again, and you kept finding the same result. How would you explain this puzzle to yourself?

You might try to figure out how apples were spontaneously reproducing in front of your eyes. You might wonder whether there was an optical illusion going on, or whether you’d somehow suffered brain damage and lost the ability to count. One thing you would not entertain, however, is whether 2+2 in fact equals 5.

That’s because the statement “2+2=4” is not actually a description of a physical thing in the world; it’s a description of a rule. And it’s not just any rule, it’s a very important one: we organize our interpretation of the rest of reality around the fact of it, and other mathematical axioms, being true.

Here’s another necessary truth: if a man is naked, he is wearing no clothes.

You can’t go out into the world and amass a body of evidence to demonstrate that, in fact, some men who are naked are clothed, and we just hadn’t realized it until you went out and found the proof. If, somehow, you were able to demonstrate empirically that some men whom we had hitherto believed to be naked were, in fact, wearing clothes, it still wouldn’t disprove the statement, “if a man is naked, he is wearing no clothes.” That statement would remain, axiomatically, just as true as it always was. You would simply have discovered that there is such a thing as invisible clothes, and the men who were wearing them were never in fact naked at all.

Like “2+2=4,” the sentence “a man who is naked is wearing no clothes,” is not a description of the world, but a rule of language. The statement means, essentially, “When we say the word ‘naked,’ what we mean by it is ‘unclothed.’” In the exact same way, the statement “2+2=4” means: “When we add 2 and 2, we call the result ‘4’.” They’re tautologies, which is what all necessary truths are.

A statement which does describe something about the world, which is not tautological, is a “verifiable statement,” or a “contingent statement.” The statement “It is raining in Los Angeles today” is one example. That sentence is empirically verifiable: it could be true, or it could be false, depending upon the evidence. It is not a necessary truth.

“The sky is blue” is another example. It may be an obvious statement, but it, too, is verifiable. You can conceive of a world in which the sky turned green. Or you can see the sky turn black every night, or gray on cloudy days. “The sky is blue” happens to be generally true, but it is not a rule around which we order the world. It is not a statement that, if allowed to be untrue, would render the universe incomprehensible. It’s a proposition that is either true or false. We can go out and amass evidence with which to confirm or refute it.

Now let’s confuse the categories. Imagine that you started treating verifiable statements like necessary truths. Let’s say that one day you decided to declare that all living beings, are, in fact, dogs.

On the surface, that’s a verifiable statement; one could go and find evidence to disprove it, such as by showing you living beings that are not canine. “What about me?”, one might say, “I’m both a living being and a human. I’m not a dog.” To which, if you were irrationally committed to the truth of your statement, you might respond: “Oh, well you’re just a human-dog.” What about that horse over there? A horse-dog. That mosquito? A mosquito-dog. That shrub? A shrub-dog. And so on.

Obviously, this incredibly annoying and childish thing you’re doing is not actually saying anything about the world around you. It’s merely describing the way you’re using the language. It’s a word game.

A lot of profound-sounding questions about epistemology and ontology, such as whether there’s a metaphysical reality that resides beneath our sensory reality, actually come down to these kinds of silly ways of manipulating language. This was one of Wittgenstein’s insights. I won’t go into that philosophical stuff here though because what’s of more immediate interest is the way they’ve been increasingly used in politics.

If you look for it you’ll find necessary truths at work in all kinds of ideologies. They often conform to the “No True Scotsman” fallacy.

The structure of the No True Scotsman fallacy is simple. Someone says, “No Scotsman puts sugar in his porridge!” You answer, “But Lachlan is a Scotsman and he puts sugar in his porridge,” to which your interlocutor responds, “But no true Scotsman puts sugar in his porridge!”

At this moment the exchange becomes pointless. You are no longer talking about tangible things in the world; instead, you’re talking about words. Your interlocutor isn’t actually saying anything about people from Scotland and their eating preferences. He’s saying something, rather, about the particular way he defines the word “Scotsman” (namely, to exclude those who like sugar in their porridge).

In left-wing politics, the quintessential “No True Scotsman” fallacy is the question of Communism, which roughly follows this pattern:

“Communist revolution leads to human equality and freedom.”

“But there have been many Communist revolutions and none of them have led to human equality and freedom.”

“Those revolutions were distorted by [corrupt leaders/unmet social preconditions/intervention by Capitalist states]. A real Communist revolution would lead to human equality and freedom.”

Neoliberals do the same thing with markets:

“A free market would correct for all inefficiencies.”

“But there are many free market economies that have inefficiencies.”

“Those markets are distorted by [corruption/unions/regulations]. A true free market would correct for all inefficiencies.”

In either case, go too far down this road and it can start to feel like you’re talking to a brainwashed cult member, like someone who refuses to give up the belief that all living beings are dogs.

The most braindead part of the discourse on the left about race and racism today also conforms to this formula. Here is a list of things from the organization Showing Up For Racial Justice that the group considers to be part of “white supremacy culture”:

Perfectionism

Sense of urgency

Defensiveness

Quantity over quality

Worship of the written word

Only one right way

Paternalism

Either/or thinking

Power hoarding

Fear of open conflict

Individualism

Progress is bigger/more

Objectivity

Right to comfort

Notice how, curiously, “the belief in the innate superiority of the Caucasian race over others” doesn’t make it into this inventory of ostensibly white supremacist beliefs. Instead it’s a laundry list of things that objectively have nothing to do with race. The only thing these random items even have in common with each other, in fact, is that they’re all purportedly bad — and even that’s questionable, since several items on the list are things most people would consider quite good and desirable.

But let’s do our best to steel man this analysis, by picking a characteristic from the list that you could maybe make a case for as an aspect of “white supremacy culture”: defensiveness.

Many Diversity, Equity and Inclusion types have observed that white people tend to get prickly when they’re accused of being racist, or of coasting by on their racial privilege, and that that defensiveness serves to shut down criticism. This is the premise of the concept of “white fragility.” Defensiveness, one might argue, is thus an aspect of “whiteness” and part of “white supremacy culture.”

But can black people be defensive? Can Asians? Of course they can. Being defensive when someone attacks you is a fundamentally human attribute. I don’t think even a DEI consultant would argue that defensiveness is unique to white people.

So defensiveness is not an exclusive trait of whiteness. It’s just a behavior that some white people engage in sometimes — let’s even grant that they do so often — that also a lot of non-white people engage in, too. It’s like jogging, or appreciating The Wire.

Now go on down the list and ask yourself the same question of each. Is a single one of these phrases particular to white people? The answer: No, not a single one.

If this were a list of “things that impede our organizational culture,” they would be at least logically defensible. But what in the world do they have to do with “white supremacy,” a phrase which, in normal language, means, well, the purported superiority of white people? A “right to comfort” is a hallmark of an ideology that seeks to rank order humanity by phenotype, and we must reject it? That’s bad news for uncomfortable non-white people everywhere.

The association between this somewhat random list of behaviors, beliefs and dispositions and a particular racial ideology is completely arbitrary. You could just as easily refer to all of these items as aspects of “rape culture” or “anti-Christian culture” or “transhumanist culture” and it would make exactly the same amount of sense, which is very little.

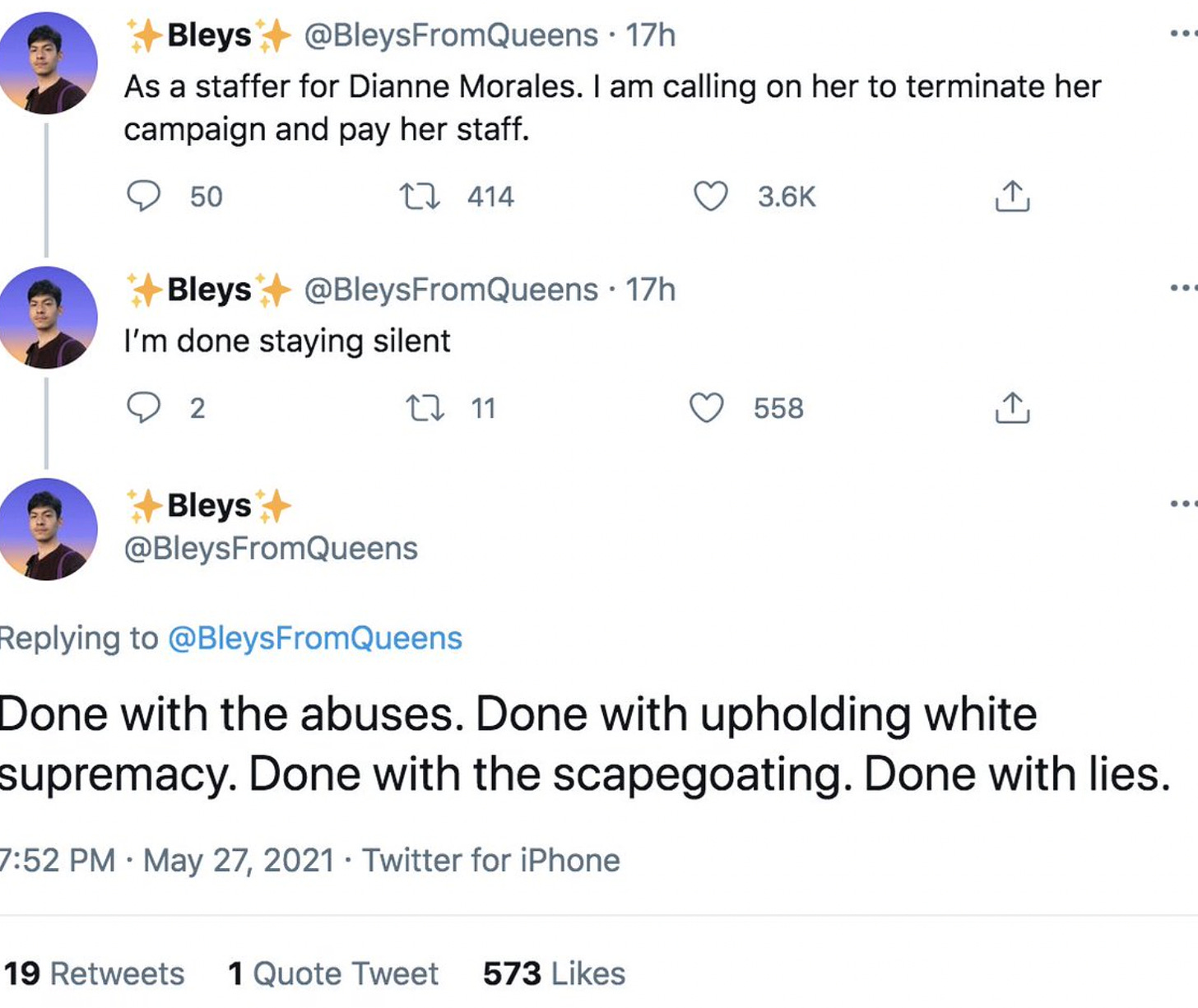

“White supremacy” is a label that at one point had an actual empirical meaning, but has since been transformed into a tautology. Anything perceived as bad is, ipso facto, “white supremacist,” whether or not it has a thing to do with race. That’s why this non-white member of the majority non-white staff of a campaign for a non-white candidate for New York City Mayor can casually grouse, in a tweet over a grievance completely unrelated to race, about “upholding white supremacy.”

It’s pure non-sequitur. What, exactly, do Dianne Morales’ objections to the demands of her campaign staff’s union have to do with “white supremacy”? Nothing — and it doesn’t have to. The signifier no longer needs anything to signify. The phrase “white supremacy” in this tweet, as in countless other contexts, is not actually being used to say anything about the world. That’s not where its utility lies. Instead, it’s being deployed to express something about the poster’s mood (outrage, exhaustion, whatever), and about the kind of person he is (the kind who says phrases like “uphold white supremacy”). It barely even counts as a verbal expression; it’s more like a token of cultural capital, like carefully placing Pikkety in sight of your web cam for zoom meetings , or gratuitously mentioning “commodity fetishism” at a DSA meeting.

On a literal level, chalking every problem in the world up to “structural racism” or “white supremacy” is just an elaborate No True Scotsman fallacy. There is no evidence you could present that would be accepted as disproof of the thesis to those who invoke it.

Imagine a scenario in which a non-white employee was held back for a promotion while a white employee was given one, and the employer was accused of racial discrimination. A conversation about the situation might go something like this:

“I don’t see what this has to do with race.”

“Not seeing race is a privilege.”

“But none of the people involved are racist.”

“Racism isn’t a personal attribute, it’s a system that we’re all socialized into.”

“But they didn’t have any racial motivations. They were just deciding based on the employee’s performance record.”

“Intentions don’t matter. Only impacts do.”

“But there were no racial impacts. What were the racial impacts?

“There’s a racial disparity. Any policy that encourages racial disparities is racist.”

“But the person who gave the promotion is black herself! How can she be ‘enabling white supremacy?’”

“There’s such a thing as internalized white supremacy.”

These responses are all boilerplate talking points from thought leaders in the world of DEI and intersectional ideology. Several are maxims invented by Ibram Kendi and Robin DiAngelo themselves. And they all serve to deflect any question demanding specific evidence for an allegation of racism. Together, they serve to transform what seems on the surface to be a verifiable statement (“This act was racist”) into a necessary truth.

Note that in this generic hypothetical example, it’s entirely possible that the promotion decision was racist. There is nothing presented here that disproves that it was racially motivated. To make that determination you’d have to look at the evidence for and against, measure and compare it, and decide from it whether the decision was motivated by racial animus or not — much as if someone said, “It is raining in Los Angeles right now,” you could go out and look at the sky in L.A. and decide, based on that, whether the statement was true or false.

But the way the phrase “white supremacy” is used in the discourse routinely disallows any such adjudication. It is deployed as a necessary truth. And that has real world consequences.

Every time there’s a high profile news report of a police shooting of a black person by a non-black officer, there is a default presumption within a certain very vocal segment of the left that it is yet another example of racist policing. That is up to and including, as we learned recently, a white officer shooting a black woman who was literally in the process of attempting to stab another black woman with a kitchen knife.

A normal, sane way to judge whether a given shooting was racially motivated or not would be to look at the evidence. Was the officer known to harbor racial animus? Is there evidence that the officer had unconscious bias? If the same scenario had played out with a white civilian, is it conceivable that different decisions would have been made? Was the officer’s life or someone else’s life at risk? Was the shooting justified by these circumstances? These are all questions that could very plausibly be answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’ depending on the case. They’re all questions worthy of an investigation.

But all that goes out the window the moment the news hits Twitter. Just as with 2+2=4, there is suddenly only one possible interpretation of the event. All contrary explanations are regarded as politically unthinkable from the outset. This is one reason why, when you argue with someone over whether a particular shooting was racially motivated or not, and begin to ask specific, ground-level questions about the immediate circumstances of the incident (Did the officer attempt to de-escalate? Was the victim armed, or was there plausible reason to believe that they were? What was said on the 911 call?), you so often face barely concealed aggravation and a series of retorts that launch you 30,000 feet into the discursive stratosphere (Are you familiar with America’s settler-colonialist history? Do you understand what it’s like to be Black in America? Did you know that police originated in slave patrols?) It’s a lot easier to defend your ground from a steep uphill position.

It’s part of a toolset of techniques, which you can be professionally trained in by DEI consultants, to neutralize the imminent threat of a serious conversation by transforming it into a vacuous word game. It is the practice of denying reality by prohibiting the kinds of basic questions that we use to establish empirical fact. It is not just anti-intellectual; it is anti-thought itself. And more each day, it is setting the terms of how we perceive reality in large swathes of the left.

I encourage you to be careful when employing the meme of thought ("Did you know that police originated in slave patrols?") which courses through many socialites' discussion regarding policing and it's history as relating to slave catching, *even if* using it to facilitate persuasion in your closing paragraph. While in the American South, this truncation of history has roots, the same may not (and should not be assumed to) apply to the entirity of the history of policing, and it's "inception", in America at large.

https://plsonline.eku.edu/insidelook/history-policing-united-states-part-1

Those individuals who claim that policing is rooted explicitly-so in the pursuit of a means to enforce structural racism, as many misled (read: propagandized) individuals believe, may appear as selfish or ignorant in their anhistorical beliefs which completely disregard the many other class, labor, economic, and law based reasons for the development of (and exploitation of) a police force within the United States.

Thank you for your post. It does well to re-ground those individuals swept up by ideological tides. I encourage all readers to remain virtuous in their discussions with those whom they disagree with.

Same goes for their "studies." They're designed to generate results that are divorced from reality and can be interpreted as racism either way.

For example, an observed discrepancy between teachers disciplining kids by race could be tested for racial bias by surveying their reasons given, then having teachers observe and react to actors recreating those behaviors, randomized by race, and with controls.

Instead, they tracked teachers' eye movements watching a video of mundane interactions between 4 kids (black boy & girl, white boy & girl) and told them to watch for phantom precursors to imaginary future problematic behavior. Teachers of all races kept an eye on black kids more. So obviously, this is evidence of racism. But what if they kept an eye on the white kids more? That'd be neglecting black kids, aka racism. And if they gave equal time to all kids? Color-blind racism, of course!

And with these meaningless, unscientific "studies," they head straight to activism and con$$$ulting.