The Other Public Health Emergency

Californians are dying in droves from drug addiction. Why does that seem to matter less than Covid-19?

Earlier this week, Michael Shellenberger and I flew down to L.A. to see if the drug addiction crisis there is as bad as it is in San Francisco. To give you some indication of the answer to that question, here are some of the people we interviewed:

• A young mother whose infant child was the victim of an attempted baby-snatching by a mentally ill homeless woman.

• A man living in a two-story wooden shack he built on a street corner in Skid Row, the upper floor of which he uses to pimp out prostitutes. He once asked LAPD officers for advice on how to install solar panels on his makeshift brothel.

• Neighbors living near a new tent encampment in front of the Venice public library who told us that local charities are pitching brand new tents on the lawn in a deliberate effort to bring more drug addicts to the site — something even the encampment’s original homeless residents objected to.

The day after I flew back to the Bay Area, I walked around San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood with a former prosecutor with the DA’s office. As on any day in the TL, we strolled past dozens of people on every block nodding off to their fentanyl highs, squeezed through crews of drug dealers crowding the sidewalk at every other intersection, passed officers interviewing a woman who had just been cut across the face multiple times with a knife, and witnessed a hand-to-hand drug deal in plain sight.

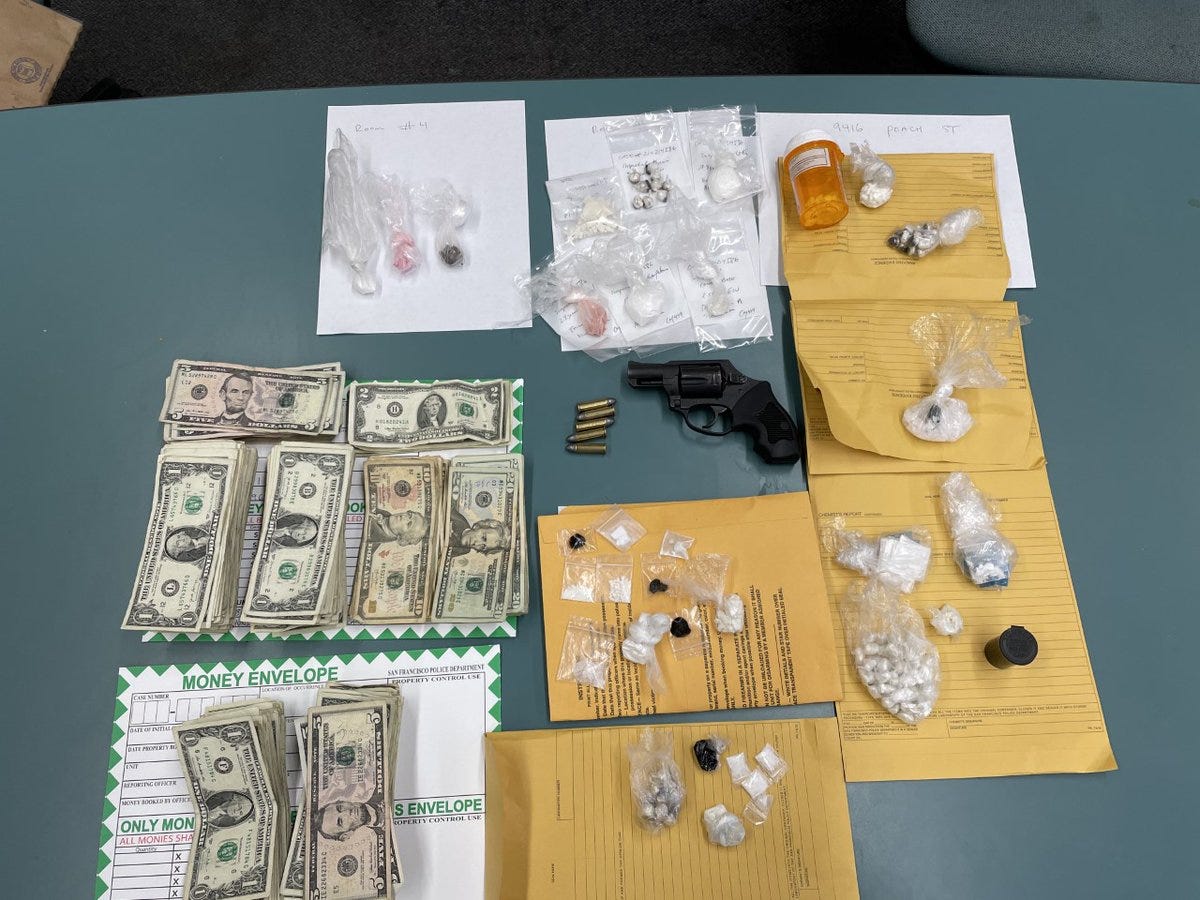

It’s true that Skid Row, Venice and the Tenderloin have all been magnets for drug use and vagrancy for decades. But it’s also true that the problem has gotten much worse, in part due to the introduction of fentanyl, but also due to California’s bizarrely permissive policies around drugs. In parts of San Francisco and L.A., it’s effectively legal to drug deal. You can do it in broad daylight, in plain view of cops. You can sell out of your trailer right in front of an elementary school, as one dealer has been doing for months on a major street in Venice — the neighbors have called 911 countless times and it’s made no difference. The dealers in the Tenderloin take the BART train in from Oakland in the morning, work a twelve-hour shift, clock out and take the BART back home, like any other worker — except unlike most workers, they’re netting $1,000 a day, tax-free.

Michael’s book San Fransicko goes into all the twisted reasons why this surreal status quo exists. Rather than go into them here, I’ll just highly recommend his book (for the TL;DR, you can check out Mike’s appearance on Rogan or at the Commonwealth Club). But I do want to note, on a personal level, how mind-bending it has been to report on both the addiction crisis and Covid-19 policies at the same time.

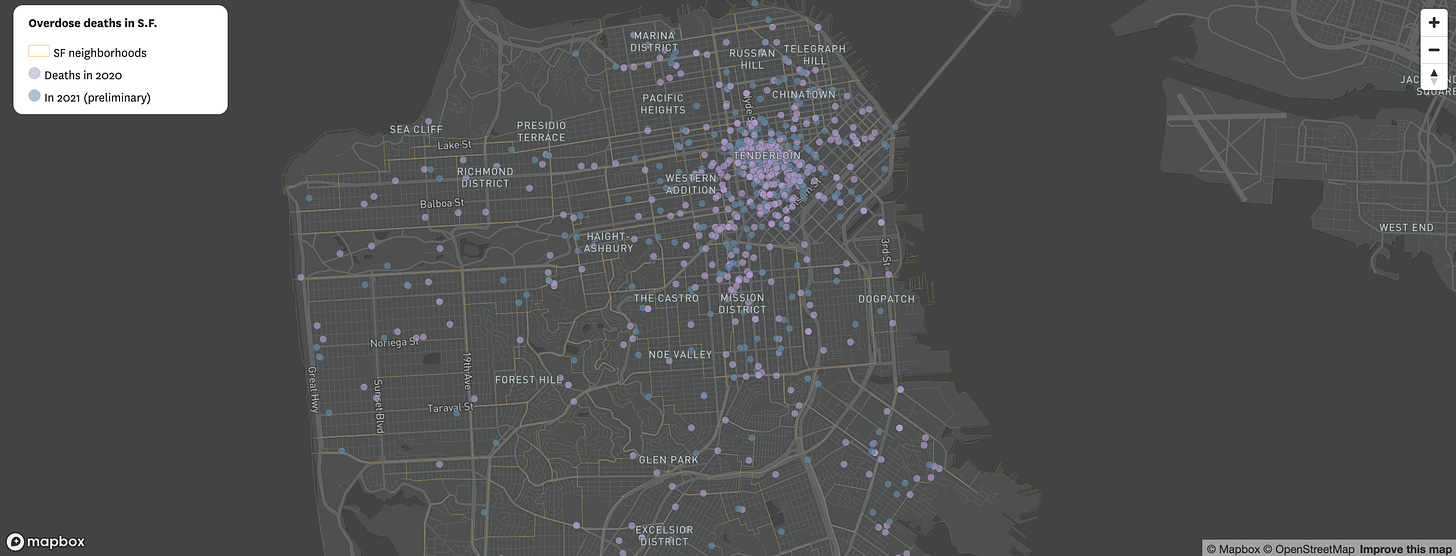

In San Francisco, nearly twice as many people have died of drug overdoses than of Covid-19 since the pandemic began. Measured strictly by lives lost, the city’s drug addiction crisis dwarfs Covid-19 as a public health emergency. And yet, you have to show your vaccination card to be seated at a restaurant, you still have to wear a mask indoors even if you’re triple vaccinated (though that restriction has been somewhat eased and is set to expire on the 15th), and teachers have staged wildcat sickouts to close down schools again. At the same time, you can openly deal and smoke fentanyl and meth even on city-supervised property, in front of city officials. Why is the answer to a lesser public health emergency a regime of draconian restrictions and moral panic, and the answer to a greater one is normalization and abstention from enforcing any laws at all?

The answer, I think, is found in the odd logic of today’s political progressivism, which divides people into two camps and applies a completely different moral philosophy to each. Homeless drug addicts are, unquestionably, “marginalized people.” That simultaneously entitles them to certain privileges and also dooms them to a special kind of indifference. To a progressive activist, the idea of coercing or pressuring a marginalized person into doing anything is morally anathema. That doesn’t just mean that it’s unethical to compel people to stop using drugs; it’s wrong even to force drug dealers to stop dealing, since they, too, are victims of “human trafficking” (they’re typically not — but I’ll get into that in a later post).

What that amounts to is, of course, a policy of impunity for crime, but also a policy that abandons people to misery and likely death. If any kind of intervention more aggressive than the provision of safe drug consumption sites and Narcan is verboten, then the public stands no chance against the coercive power of addiction. As more than one former addict has told me, it’s almost impossible to get and stay clean without some outside force cutting you off from any other option. By voluntarily relinquishing that tool, cities like San Francisco are just giving up on the drug addicted. The city’s policies amount to giving palliative care to patients whose conditions are far from terminal.

Ordinary housed and non-addicted San Franciscans, on the other hand, are, relatively speaking, comfortably non-marginalized, which is to say “privileged.” For those people, the sky is the limit when it comes to implementing coercive measures to safeguard, ostensibly, the public good. Shame them, threaten their jobs, kick their kids out of school — nothing is off the table when it comes to forcing the privileged non-compliant to fall in line.

In this attitude are the seeds of authoritarianism. But at the same time, the hysteria around the urgency of protecting each and every life, the total intolerance for even the slightest risk to public health, stands in shocking contrast to the somber passivity with which the city tolerates two deaths a day from drug overdoses.

But this contrast is of a piece with the way in which “marginalized people” are routinely perceived by progressive activists today: as both more and less than human. Like Rousseau’s “noble savage,” the marginalized victim is an idol made incarnate, a lefty team mascot. He is at once greater than mere mortals in terms of his moral and symbolic worth, but practically without value at all as an actual, flesh-in-blood individual. The same moral logic that allows people to rot to death on the streets in the name of defending their inherent dignity and autonomy is that which tolerates people being victimized by crime in order to provide them protection against the police that they never asked for in the first place.

So the twin public health emergencies, in the progressive imagination, occupy two separate symbolic tiers. In the case of the pandemic, it’s people like ourselves who are at risk of dying, and people like ourselves who are, allegedly, putting us at risk. No sacrifice is too great to protect this population, and no demand too great to ask of us to ensure that protection. In the addiction crisis, it’s the left’s “victims” whose lives are at risk, and other “victims” who are exploiting and perpetuating that risk. In that case, nothing can be demanded of the victims — neither the ones whose lives are at risk nor those who are putting them there. And yet, those deaths count for so little that not even the slightest price in political purity is worth paying to save them. So the status quo persists and grows, and the body count continues to mount.

The main way opioid and meth addicts get clean is by getting arrested. The majority of people, especially those who read The New York Times and its ilk, don't know this.

You're probably right, but there is another dynamic: drug addiction is SEP (someone else's problem), while COVID is an allegedly deadly virus anyone can catch. Especially in America's urban centers, people are scared shitless of catching COVID.

Contrast this with what I believe was a viral emergency far worse than COVID in terms of death and sickness: the AIDS crisis (someone else can look up the numbers, but until the mid-1990s AIDS featured 100% mortality). I was a young man at the time, and as I recall we did not upend society to "do something" about AIDS, because in fact AIDS was very easy for most people to avoid. I know I never worried about it. AIDS was SEP.

You avoided AIDS by not being sexually promiscuous. You avoid drug addiction by not taking drugs. The media and political classes have convinced the credulous that COVID is almost as dangerous as HIV, and anyone around you can be a carrier. There is no escape!