If you spend any amount of time in left-of-center political circles you get accustomed to hearing educated, middle-class liberals describe Republican-leaning blue collar Americans as “voting against their interests.” The truism goes back to Thomas Frank’s What’s the Matter With Kansas, or even further, to the Marxist diagnosis of “false consciousness” to explain away the existence of reactionary proletarians. Why, these liberals wonder aloud, would an impoverished wage slave lend her support to a political party known for championing the rights of billionaires to stash their fortunes in offshore tax havens, and for strangling the last life out of the comatose body of America’s welfare state? Could it be that they’re “clinging to their guns and religion,” as Obama put it, or that they’re closet white supremacists, as millions of Democrats came to suspect in the Trump years?

Curiously, those liberals rarely ask the same question about themselves: why do so many college-educated, high-income, high-status professionals support a party ostensibly devoted to taxing affluent people like themselves to pay for social services for which Democratic-voting doctors, lawyers, professors and their children will never be poor enough to qualify? It’s one thing for indigent or working class Democratic voters to vote Democratic, but if votes are as simple as economic cost-benefit calculations, is it not the height of irrationality for the party’s white collar strata to vote in solidarity with the poor? Are they not voting against their interests, too? What are they clinging to?

It’s much more comfortable to cast an anthropological gaze upon others than upon oneself. It’s easier to look at our own motivations as uniquely inspired by our humanity, our intellect and our personal character, while reducing others’ to the mechanical responses of lab rats in Skinner boxes. But there is, in fact, a better explanation than personal virtue for why economically comfortable liberals tend to reflexively side with the poor and the oppressed even when it comes at their own financial expense. And it aligns squarely with their class interests.

A few weeks ago I wrote about the late French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, and how his insights help explain why our media sucks so hard. Bourdieu is one of those writers whose ideas, once you get your head around them, you see, easily, wherever you look, like a stereogram after it comes into focus.

As I mentioned in that earlier piece, Bourdieu’s conception of power is pretty intuitive: he conceives of it as capital. In an economic context, that’s a universally familiar idea. Capital is money that makes money. Money alone can buy you stuff, but it’s capital that bestows real economic power.

Economic capital functions in more or less predictable ways within a market. You can invest it and reasonably expect to accrue returns on those investments. You can be shortsighted, or greedy, or insufficiently risk-averse, and squander it. We all understand these rules, more or less.

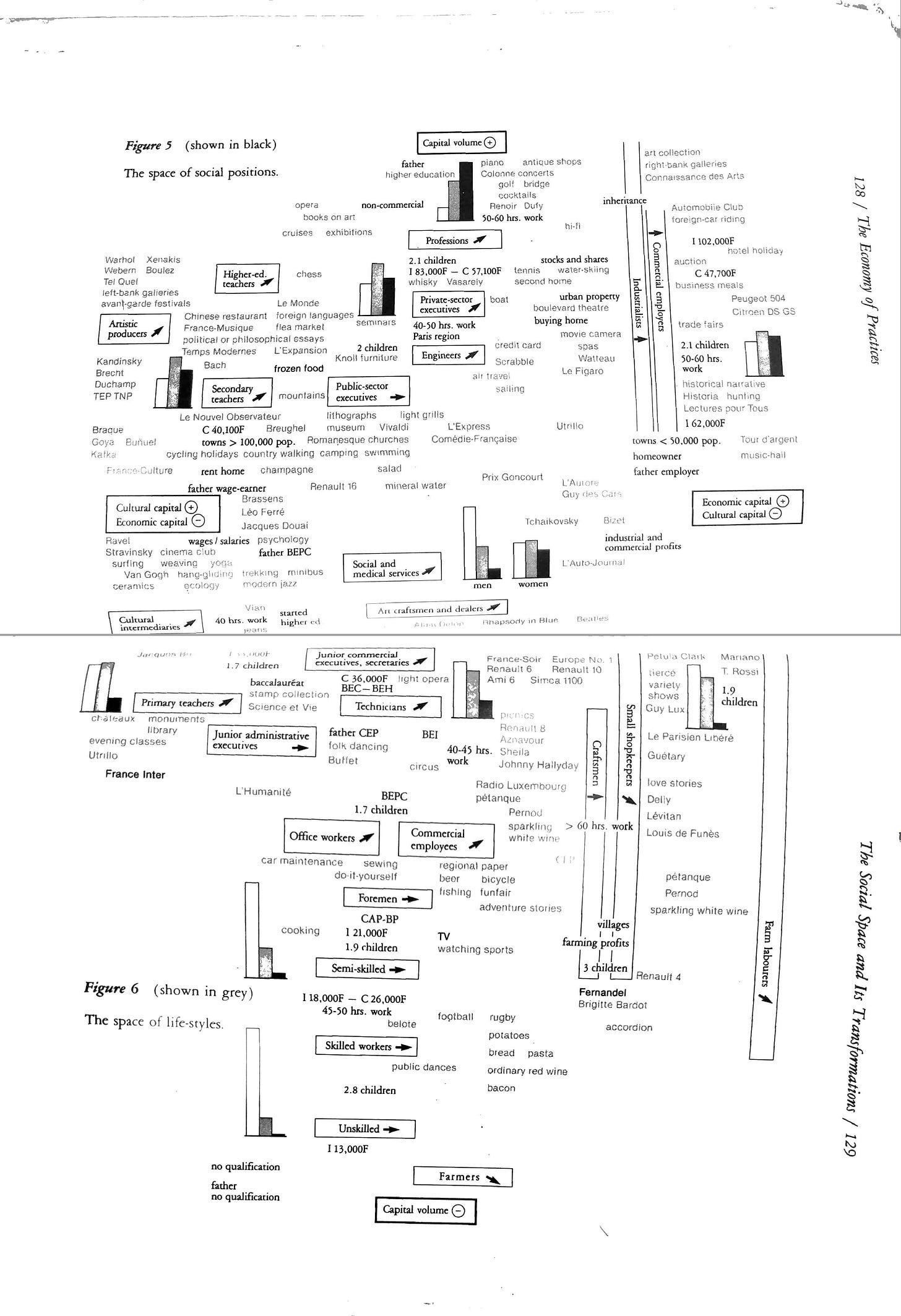

Bourdieu expanded on this conception of markets and capital by perceiving the same dynamics at work in every nook and cranny of our social lives, not just our economic activities. That is to say, he discerned the existence of other forms of capital at work, not just the economic kind. Most famously, he conceived of cultural capital.

“Cultural capital” has become a household term since the time that Bourdieu coined it, so it may need no explanation. But, briefly, it refers to the cultural knowledge you accrue that enables you to navigate your way around a specific social milieu. If you work in Silicon Valley, that could be fluency in a particular corporate lexicon, a working knowledge of cryptocurrency, and expertise in intermittent fasting. Or if you’re poor and you live in an urban setting, it could be a familiarity with street lingo, an understanding of the local hierarchy of those with power and influence, and a knowledge of how to navigate social service bureaucracies. Note that these currencies are not necessarily exchangeable across milieux. Talking about OKRs and the 16/8 method is going to get you about as far on “the streets” as understanding which hoppers run which corners is going to get you at a VC firm in Menlo Park.

Cultural capital, Bourdieu observed, is one of the fundamental means by which members of the elite pass down their class status to their children. Obviously, there’s an even more straightforward way of making sure your kids remain in your social class: by giving them your money. But that mostly doesn’t happen until you die. While you’re still around, the transfer typically takes the form of cultural capital, principally by way of education.

In the United States we’re accustomed to thinking of education as the great equalizer, but Bourdieu saw it differently. In fact, he saw it as the reverse: he saw schooling as the primary tool with which we sort ourselves by social class.

If you went to a tracked public high school you’ve seen it plainly. On the lower track, schools prepare students for a future as, at best, a member of the working class. Aside from basic literacy and numeracy, students are instructed in vocational classes like wood shop and machine shop, and practical life management courses like home economics. Perhaps the main lesson teachers attempt to impart to lower track students is obedience to authority. Meanwhile, on the upper track, students are prepped for a lifetime membership in the bourgeoisie, through STEM classes that train them in abstract thinking, in taste-making fields like English literature, art, and music appreciation, and in extracurricular activities that emphasize values of leadership, creativity and entrepreneurial spunk.

As everyone knows, families in the elite classes make enormous financial investments to ensure that their children get the right kind of education, either by moving to affluent suburban neighborhoods with the highest performing public schools, or by forking over hundreds of thousands of dollars in private school tuition, or both. In doing so, Bourdieu observed, such families effectively invest their economic capital into their offspring in the form of the cultural capital their children accrue by way of such an education.

That cultural capital includes instruction in a particular way of speaking the English language, i.e., “properly.” It includes a working knowledge of, and a cultivated reverence for, the canonical artistic creators of Western literature, art and music. It includes an inculcation of the tastes, preferences, assumptions, prejudices, humor, and values of the elite classes. These days, an elite education has been updated to include a cosmopolitan appreciation for the cultural products of exoticized, “marginalized” peoples, from Native American religious rituals to hip-hop culture, alongside the instillment of a certain ostentatious, condescending concern for the well-being of the underprivileged. All of these manners and dispositions are demonstrated to others later in life in the ease with which the recipients of such an education carry themselves in elite circles, and the natural self-confidence with which they wield power and authority — as if they were bred for it, because they were.

The fact that education is such a long, drawn out process is critical to its function as a reproducer of social class, especially when it comes to the challenge of distinguishing the true, “old money” elite from the “new money” strivers. The social systems Bourdieu investigated most closely were the ones all around him — those of twentieth century France. Granted, the upper crust of French society is a bit snootier than the upper crust of American society, but the concept of old money versus new isn’t entirely foreign to Americans. In the U.S. as in France, the story is the same: newly rich but socially insecure arrivistes strive for acceptance among the old, traditional, hereditary elite, while the old money families take every opportunity to expose the arrivistes — whose wealth threatens their always tenuous monopoly over prestige and status — as poseurs. No matter how much money the nouveau riche amass, it’s never enough to be fully accepted by the old regime. A lifestyle marked by conspicuous consumption not only fails to secure them entrée; it’s actually counted against them as yet another telltale sign of their crude, amateurish relationship to money, and their pathetic, desperate thirst for approval. The harder they try, the harder they learn the old adage that you can’t buy class.

Education is the ultimate proof of one’s rightful place among the traditional elite, because only the cultural capital accrued from years of immersion in an elite education can demonstrate definitively that you do not merely possess wealth; you grew up in it. The subtle inflections of language and manner, the social graces, the easy familiarity with obscure avant-garde writers and artists, the ironic detachment, the cultural signifiers casually name dropped at all the right times: these are things that cannot be faked, or at least not for long.

So while economic capital can, over time, be converted into cultural capital by way of education, and cultural capital can be converted back into economic capital by way of securing the requisite academic credentials that provide access to higher income professions, the two forms of capital are also often in tension with one another, like competing national currencies.

It is this tension that sheds some light on the question of liberals and their reflexive solidarity with the poor and the oppressed.

While in some rarified corners of the world, the cultural capital of hereditary wealth competes with the economic capital of the newly rich, as a general rule there is no contest: Economic capital is the dominant form of power, full stop. Money may not be able to buy you class (and even that conventional wisdom is being disrupted by the California-style oligarchs of the tech industry), but it can buy you pretty much everything else, and who needs the approval of snobs when you run the universe?

Everybody knows this — most of all, to their consternation, those who enjoy an abundance of wealth in cultural capital, and a relative paucity of money. Bourdieu situates these fortunate/unfortunate people in “the dominated fraction of the dominant class.”

Perhaps the platonic ideal of the rich-in-cultural-capital/(relatively)-poor-in-economic-capital figure is the college professor. Steeped in esoterica, rarified in his dry and knowing humor, virtuosic in his ability to speak in complete paragraphs, skilled and subtle in his name-dropping, deeply moved in his appreciation for the arts, he is a maestro in the art of dinner party cultural pageantry. And yet his decades of toil to hoard cultural capital affords him no more than a comfortably middle class existence.

He looks with barely concealed contempt upon his brother-in-law, the corporate vice president of a bank, with his vacuous MBA — a degree that took barely two years to earn — and his ridiculous house with its massive carbon footprint. His brother-in-law who knows nothing of life, culture, politics, or the world, who reads self-improvement books when he reads at all, who would rather take a ski vacation in Aspen or get drunk in Cabo than take a sabbatical in India or Cambodia or Berlin.

He would never trade places with that douchebag — what is an outsized ego and an over-inflated bank account compared to the life of the mind? — but he can’t help being perplexed by the rewards, both material and social, that the world never stops dumping in his lap. No, he’s not jealous, he’s just...disappointed. Disappointed in the debased values of this hopelessly stupid and self-centered society.

His brother-in-law, the professor tells himself, is the very incarnation of everything that’s wrong with our country today. His vulgar pursuit of money, his indifference to the welfare of others, his ignorance of what is truly of value in life: this is the depraved side of human nature that’s killing the planet and sickening society. It’s men like him (“and it’s almost always men”) who run the world, and as long as that’s the case, we’re all doomed.

The college professor, the journalist, the critic, the curator, the software engineer, the hospital administrator, the grant officer, the civil servant: they all share in this general bias. They’re united in their collective yearning for a world in which the educated, the enlightened, and the credentialed made the rules instead of the boorish capitalists and their political lackeys who actually do. They pine for a world in which not money but cultural capital makes the world go around.

But it’s not for themselves alone, the professional classes are convinced, that they wish for such a world. It is for society’s downtrodden, those who have been exploited, marginalized, and oppressed by the reckless power of economic capital. It is for the powerless, the boosters of cultural capital declare, that they should be bestowed power.

Nothing has ever made them more certain of this than the election of Donald Trump.

For some thirty years, the demographic pillar of the Democratic Party, and of political liberalism generally, has been shifting from blue collar workers to educated professionals. For most of that time, non-white working class voters have stuck with the Democrats, largely out of disdain for the race-baiting tactics of the Republican Party. But even that has begun to change. Every election cycle, the split becomes clearer: the dividing line between Democrats and Republicans is the line between the college-educated and the non-college educated.

It seems, at first, paradoxical that over most of that time period, the Democratic Party has become increasingly left-oriented even as it has shed its working class base. Why haven’t the Democrats made themselves into the party of property tax cuts, law and order, child tax credits, and other interests of their educated professional class base, instead of the party of universal healthcare, racial justice, and the Green New Deal? Why didn’t Bill Clinton’s New Democratic Party last?

But that question presupposes that there is only one form of capital at work, the economic kind. When you take cultural capital into account, and consider the rivalry between those whose status is derived from it and those whose status is derived from money, the left-leaning slant of the professional classes starts to make sense. The very identity of the brokers of cultural capital is rooted in their conception of the brokers of economic capital as the source of all that debases the world. Speaking against them and their deprivations is speaking on behalf of all of humanity.

And to those who revere cultural capital, no figure better embodies the vulgarity, the parochialism, the small mindedness, the boorishness of naked economic capital than Donald Trump, the consummate arriviste.

Under the Trump presidency, a vast and amply-funded progressive political infrastructure sprung forth. Overnight, scrappy new activist groups were blown up into charitable Goliaths, while staid old lefty advocacy organizations were re-baptized with a new mission. The language of revolution was on the lips of former foreclosure lawyers, millionaire wives of hedge fund directors, and foundation grant officers. The media was transformed into an ideological propaganda apparatus, and the social media platforms that more or less control public discourse were made into the technocratic establishment’s enforcers of scientific truth. Between the frenzy of activity and the hyperbolic language, it felt like a seismic shift was underway.

But despite the radical rhetoric, the most momentous victories this new civil society has so far achieved have benefited not the poor, but the professional classes themselves, whether it’s the diversion of corporate profits into the creation of a vast new industry of specialized HR consultants, or the funding of new academic departments, or the embrace of college student debt cancellation as the left’s signature cause.

These goals and triumphs have done next to nothing for the poor, and have constrained the power of corporations and billionaires not a whit. All that this historic explosion of political activism has amounted to is an aesthetically revolutionary movement by, and for, the middle management tier of America’s power elite. It’s a compromise the C-suite tier can happily live with, which is why they’ve joined hand-in-hand with the liberators storming the barricades.

This, sadly, is the struggle of our moment: not an epic battle between the world’s elite and its destitute, but between two rival factions within the elite, with one side cosplaying as the vanguard of the oppressed, and the other letting them enjoy the act.

To some extent, we all see through it already. That’s part of the reason why, all over the world, the populist movements that are emerging from the working classes themselves, from the Yellow Vests to the Indignados, have been so ideologically heterodox. Nobody who’s interested in actually confronting power is taking their marching orders from fellows at the Ford Foundation and Harvard’s Kennedy School. On an instinctive level, everyone understands that the culture capitalists aren’t fighting for us. They’re fighting for themselves.

All valid except the premise that students devoid of cultural capital are destined to take vocational courses and enter the working class. Those courses are quickly disappearing from high schools as students are told they must go on to college. Students who choose instead to go into a trade or the military are not left behind or subordinated, they have chosen a different path -- a path which will likely be rewarding and substantial. These are the bedrocks of our society, and their perspective on life is as valid -- if not more -- than the overpaid, eloquent university professor who can't change a flat tire.

Exactly, you nailed it!