I enjoyed Don’t Look Up as popcorn entertainment, mostly because the acting from its A List stars was superb. I’m not going to read a whole lot further into the film than that, because if I do, I’ll be forced to articulate all the ways the climate change analogy falls apart upon inspection, which other writers have already done. Suffice it to say it was a good movie; I recommend watching it. I don’t recommend taking it as the political lodestar of our time, or comparing it to Spartacus or Dr. Strangelove or even In The Loop.

I would say, however, that if I were to write the screenplay for a similar movie today, there would be a whole host of new ideas to bring into the mix that have come to light because of Covid.

I’ve read a fair number of books on climate change, including David Wallace Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth (highly recommend), just about everything Naomi Klein has written on the subject, and even cli-fi novels like Paul Kingsnorth’s Alexandria and Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife. I have been diligently scared shitless by all of these books. That fear has become even more profound since I had my first child two summers ago.

Obviously I had no idea that in my lifetime, we’d live through a fire drill of imminent global catastrophe. But that’s what’s been happening every day for the last two years.

What we’ve seen from that experience has complicated and compounded my climate-related anxieties with new questions and concerns. I’m uneasy acknowledging it, but the first of these concerns is this: I’ve found myself newly doubting the validity of the doomsday messaging around global warming that I’ve consumed so much of.

When I say “doubt,” I mean just that. I’m not convinced that those projections are specious; I just have found some reason for skepticism. That skepticism comes down to two things: 1. I can’t un-witness how cavalier the scientific establishment has been with their uniformly dire expert opinions on Covid-19, and 2. the pandemic has revealed a weird and macabre thirst for the eschaton among certain people — a tendency that seems recognizable among those most fearful of climate change, as well.

The many ways in which scientists have played fast and loose with their judgements and opinions on Covid-19 hardly needs recounting. But for me personally, a few moments come to mind. One was the plainly political denialism around the lab leak hypothesis. Another was the mind-boggling stupidity of the open letter signed by nearly 1,300 health care professionals insisting that public demonstrations against the police were not a threat to public health while anti-lockdown protests were. The third was less of a moment than just the general agglomeration of chaotic, arbitrary, clearly politically-motivated decisions around school closures dressed up in the language of meticulous, evidence-based epidemiology.

The eagerness on the part of what feels like a very large swathe of the professional managerial class to believe only the most apocalyptic interpretations of events and to dismiss everything else as “disinformation” is harder to pin down. But I’m far from the only one to have noticed it. I still have no satisfactory explanation for this, but over the course of the pandemic it clearly warped the public’s capacity to soberly assess the scale and acuity of the public health threats we faced, which in turn hobbled our ability to devise responses that were measured and proportional and not symbolic, punitive, authoritarian and wildly overreaching.

Taken together, these two tendencies have left me wondering whether we’ll do the same as we inch up global temperatures by 1.5, 2, and 3 degrees Celsius, and if perhaps we are already doing so. Are the climatologists who issue these grave warnings resisting the urge to exaggerate — an urge that, on a human level, I can somewhat understand in the face of a public that seems insanely indifferent? And are we sure that the part of the public that’s most open to those warnings is not engaging in some kind of weird Millenarian role-playing, of the kind that we’ve become accustomed to since the pandemic began? I don’t have the training to read climatology papers myself and reach my own conclusions about their validity (though I once tried, spending two days listening to lectures I didn’t understand at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco), so like most people, I have to just listen to how the scientists articulate their conclusions to lay audiences, and trust that they’re doing so in an accurate, empirically defensible way. But after what I’ve seen of the flagrant admixing of scientific conjecture and political grandstanding during the pandemic, I’m more uneasy about giving the experts that benefit of the doubt. My confidence in science is undiminished, but I’m not so sure I trust scientists so much anymore, at least when it comes to scientific issues of huge social and political significance.

Again, these are just concerns. I’m not persuaded that we’ve all been duped. I’m no more a “climate denier” for indulging in this modest skepticism than I am an “anti-vaxxer” for opposing mandates. But I do wonder.

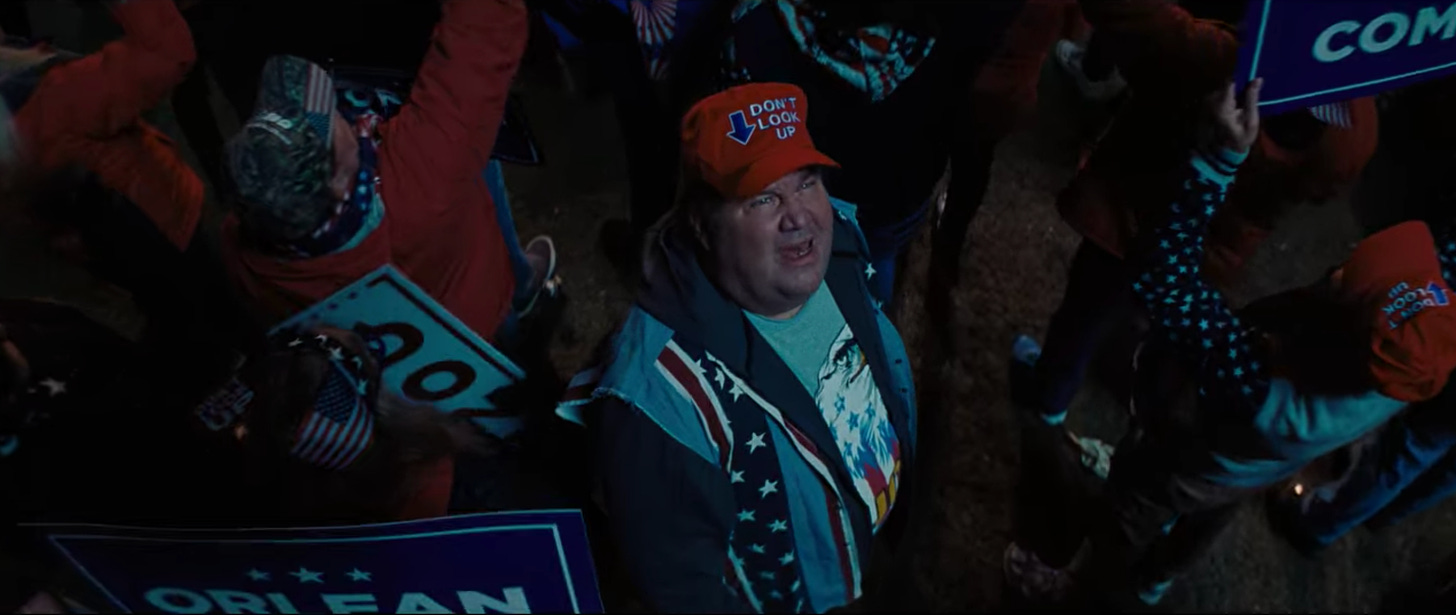

This gets me to what my version of Don’t Look Up would look like. Predictably for a Hollywood flick, some of the biggest dumb-asses in the movie are the Joe Six-Pack extras who blindly follow the cynical, reactionary politicians who are stirring up distrust of the “experts” for their own narrow ends. These hostile, indignant marks are obviously stand-ins for climate deniers — or, now “anti-vaxxers”; it’s not even subtle. I begrudge Adam McKay for taking this cheap shot not at all: the movie is parody, and this is what parody does. But if you’re going to lampoon the knuckleheads on the other side, you should do the same to the ones in your own column. That’s what Armando Ianucci would’ve done.

And from the experience of the pandemic, we know all too well that knuckleheads abound on both extremes. Among the hoi polloi, the dimwits on the “believe the experts” side would include people who — well, I would say people who exaggerate the threat of the impending collapse, but since McKay made this a movie about a meteor literally obliterating the planet on a date certain, he’s cleverly forestalled that line of critique. But it would also include those who accept inevitable doom but then almost revel in it, using their smug certainty to score points on everyone around them who’s inadequately enlightened. And it would include people who practically welcome the asteroid as some sort of moment of moral clarity and final judgement — a group that the 1996 flick Independence Day doesn’t forget to send up.

On the egghead expert side, it would include newly minted, social media-addicted micro-celebrities whose soothsaying is richly rewarded by hundreds of thousands of RTs and faves and dozens of podcast guest appearances. On this, Don’t Look Up does better. If the character Leonardo DiCaprio plays is meant to even obliquely reference Anthony Fauci as the well-meaning scientist who starts to believe his own media hype, then I applaud the satire (that’s a big if, though).

But that analogy, too, collapses when Dr. Mindy starts telling the public not to worry, as the grown-ups have the situation under control. Under today’s media incentives, the most publicity-seeking and social media-addled of the expert class are incessantly invited to fuel the terror that brings them the attention they seek, not to temper it. Dr. Mindy would be marching on stage at his talk show appearances with a bunch of charts and graphs showing how the the meteor was likely to arrive even sooner and be even more destructive than previously thought, and encouraging viewers to continue to obsess over his every uttered word if they want to stand any chance of survival.

Over the last forty years, there has been a massive and obvious incentive on the part of certain extremely rich companies to put everyone’s minds at rest about the coming cataclysm of climate change. We all know this; the industry of climate change denialism is one of the most widely reported scandals on earth. But things have changed quite a bit. Climate denialism has waned in the face of overwhelming evidence, but more importantly, the incentives of traditional, digital and social media have radically shifted with the collapse of the advertising-based revenue model of mass media.

Today, the incentives are aligned in favor of alarmism. Everything that was once, at most, an intractable social problem — police violence, prejudice against transgender people, hostile foreign governments meddling in our domestic affairs, conspiracy theories, unauthorized mass immigration — has become fascism, genocide, white supremacy, an infodemic, American carnage. We drown in hyperbole every time we open a browser, watch cable news or turn on NPR. It all points us in the same direction: toward entropy. We distrust our neighbors and despise our political adversaries, we’ve lost faith in our institutions and in the legitimacy of our elections, we have more anxiety than hope for our children’s futures, and we all wonder how long we can endure as a single nation. We’re stuck in a bottomless mire of catastrophic thinking, a nationwide clinical depression.

The pandemic has made it all acutely worse. We have not pulled together as a country to meet a common threat. We have not expanded the reach of our compassion to measure up to our awareness of the breadth of suffering created by this virus. We have not seen a reality so stark that the scales fell from our eyes, and we were forced to finally listen to the experts, nor have those experts met the gravity of the moment by transcending the pettiness of our divisions and rescuing us from our parochialism; instead, many of them have sunk to the level of social media influencers, adopting the histrionics, ego contests and catty clapbacks of TikTok stars. As a culture, we have only become pettier, more spiteful and more certain of our orthodoxies and prejudices. We have not risen to the occasion. This is not Independence Day. On that lesson, too, Don’t Look Up gets it mostly right.

But ultimately, Don’t Look Up stays safely in its political box. The bad guys are the witless, scheming politicians, the soulless, scheming corporate oligarchs, and the vain, scheming media. The victims are the seduced scientists and the duped public. The good guys are Jennifer Lawrence, basically, and Dr. Teddy whatever NASA guy.

Nowhere to be seen are the journalist hype artists, riding the wave of public fear to unprecedented heights of fame, page views, and new subscribers, or the smug, know-it-all scientific dilettantes, lording their hoarded factoids over their unschooled relatives and colleagues on Facebook, or the liberal equivalent of the movie’s foamy-mouthed partisans, weaponizing every disagreement to heap disdain on the troglodytes on the other side.

We know better now. We know that as the global temperature ratchets upward, we will have all of these people all around us, every day. Some of them will achieve fortune and influence, and will use those resources not to summon up our collective spirit, but to pry our social fractures even deeper and wider. If climate change is as bad as we fear — and, again, I’ve been newly uncoupled from that blind assumption — then we will likely destroy each other well before nature does.

I've had a similar evolution from good progressive repeating all of the right talking points to disillusioned skeptic.

For me, the seed of skepticism with mainstream narratives began with Black Lives Matter. As a criminal defense lawyer, I have more firsthand knowledge of the world of crime and policing than the average educated liberal (though still less than the average resident of a high crime neighborhood). The cold hard fact is that there is a disproportionate amount of endemic violence in lower income black communities, and this higher baseline level of violence explains the disproportionate rate at which black suspects are killed by police. The BLM narrative denies this reality, and then lies about the facts of the individual cases ("Hands up, don't shoot"). Nonetheless, the media and academia accepted and promoted this narrative with enthusiasm, often using the patently dishonest formulation "Black people account for X% of police killings despite making up only 13% of the population."

By the time of the Floyd killing, I was still uncritically accepting the Covid narrative. I didn't want to put in the time and energy required to "do my own research." I thought Bret Weinstein had lost his bearings when he was still pushing the "debunked" lab leak theory. But then all of a sudden the lab leak was back at the mainstream table. Around the same time (if I recall the timeline correctly), Bret had Kirsch and Malone on his show. Given that it looked like Bret had been right to continue talking about the lab leak, I figure I'd give it a listen. I was skeptical, but as I went deeper down the rabbit hole, more of their claims turned out to have quite a bit of evidentiary support. Moreover, the counter-arguments on the "fact check" sites were obvious hand waving and propaganda. From that point, I radically questioned all of the assumptions I had taken on board in the course of my liberal education.

Climate change alarmism is a tough nut to crack because it all relies on modeling. If there is anything we all should have learned during Covid, it is that models have approximately zero evidentiary value. They mean nothing. Complex systems defy our modeling capabilities. So I have to say at this point I am a climate agnostic. Environmental devastation is an apparent fact, as are steadily rising temperatures (I think?) but the narrative about imminent collapse of the ability of earth to sustain human life (which is all based on the models) is no longer credible to me.

Notably, each of these issues (BLM/equity/social justice, climate change, Covid/pandemics), if we accept the mainstream narratives, demand totalitarian structures to tackle them. It is this desire for power and control that drives these narratives, not the facts. This is why they are so stubbornly resistant to facts and logic. My rule of thumb going forward is: If some supposedly urgent problem calls for a totalitarian solution, we are probably being lied to.

In Don't Look Up (which I haven't watched yet), the solution was technological, not totalitarian, making it a very poor analogy to the contemporary problems we are being urged to worry about and the totalitarian solutions we are being urged to accept. In that respect, it is not only a poor analogy, but amounts to dangerous propaganda. If you do not proclaim that the sky is falling, surrender your rights to the authorities, and demand that others do the same, you are the Joe Six-Pack troglodyte. And who wants to be a Joe Six-Pack troglodyte? Given the alternatives, just call me Joe.

I always appreciate your pieces, and I mean that in the many senses of the word, but you have outdone yourself. Thank you.