I was honored to be selected a few days ago by Freddie de Boer, a writer I have admired for years, as his Substack of the Week. To those who subscribed on Freddie’s recommendation, welcome. I hope I can live up to the flattering expectations he set; I will certainly labor hard to do so. —LW

A couple of years ago, before it was effectively won by Assad, I used to follow the Syrian civil war closely. By that I mean I read about it a lot and then got in fights about it on Twitter. Outside of the actual battle zone, that seemed to describe about ninety percent of what people who cared about Syria actually did to espouse their cause. The fights, as you can probably imagine, became incredibly nasty. I used to joke that the actual Syrian conflict itself was a proxy war for the grudge matches on Twitter.

The pattern went something like this: a bunch of people (including me) were of the opinion that Assad was a tyrant on a world historical level, a mass murderer on the order of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao, and that the world was effectively letting him get away with atrocities that we as a species had pledged over and over to never allow to happen again. On the question of what to do about it, though — which ultimately came down to whether or not to call for increased U.S. military intervention in the conflict — we tended to prevaricate. Partly that was because we were mostly anti-war liberals, and we were genuinely uncomfortable arguing in favor of using force as an instrument of humanitarianism. Partly it was because on some level we were aware that American intervention was, inexorably, the logical conclusion of the argument we were making that the violence being perpetrated on the Syrian population was so egregious that it justified almost any means of putting an end to it. And we knew, as a practical matter, that once we conceded that point, we would be plausibly branded neocon hawks and the debate would be lost.

On the other side of the argument were those who were dead set against any American involvement in the war no matter what Assad did. People in this camp routinely accused those on our side of being Western imperialist stooges disguised as bleeding-heart do-gooders. They would charge us with being in cahoots with the CIA in engineering a “regime change war” against the Syrian people and state. Some of them would even defend Assad as the victim of an international conspiracy. Anyone who picked up arms against the regime, and anyone who sympathized with them, were branded jihadist terrorists by these militant anti-interventionists, including civilians being bombarded by Syrian helicopters and Russian fighter jets.

The debate would quickly degenerate into each side shouting names at each other: “Assadists” vs. “imperialists.” Then, as the acrimony spread into everyone else’s timelines, hundreds of people who knew next to nothing about the conflict but were personally aligned with various individuals on either side of the dispute for entirely extraneous, social media-related reasons — maybe they were fanboys of the same podcast, or fought in the Twitter trenches together for Bernie Sanders — would join in on the name calling. These reinforcements would mimic the talking points of those to whose aid they were riding, and those talking points would begin to shape their own impressions of what was actually happening on the ground in Syria: which foreign nations were aligned with which militias, what was and what was not in evidence about alleged chemical attacks, the order of events that precipitated the taking up of arms, et cetera.

Soon, the digital battle lines were demarcated. On each side of those lines stood a handful of people steeped in encyclopedic details about UN reports, chemical weapons forensics and geopolitical machinations. Behind them stood thousands whose basic, factual understanding of the actual, physical war was entirely a function of who they happened to regard as their friends and allies on Twitter. Rather than the reality of the war determining who stood on which side of it, for most people, it was the other way around: the composition of the feuding camps that happened to coalesce around each side for entirely tribal reasons determined what one believed to be the facts of the conflict itself.

At the end of the day, it didn’t really matter anyway. For better or for worse, U.S. military policy is by and large the exclusive province of the executive branch. As such, it’s insulated from mass political pressure and is more or less impervious to the vagaries of Twitter. The pitched battles of Twitter’s #Syria thus amounted to little in terms of the actual country of Syria, or anywhere else in the real world, for that matter. They were a tempest in a teapot. But that’s not so when it comes to matters of domestic policy.

More and more, the proxy war dynamics of #Syria have come to characterize all of our politics. Unlike in the digital debate over the Syrian war, however, in the domestic arena these dynamics have potential real world impacts. Take, for instance, the Democrats’ and the Republicans’ Freaky Friday body swap on their respective public postures toward the military last week.

Last Wednesday, in a House hearing over the Defense Department’s budget, Republican Representative Matt Gaetz interrogated Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin about the teaching of “critical race theory” in the armed services. Before Austin could answer the question, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley, who was also participating in the hearing, tried to interject. Gaetz cut Milley off, insisting on hearing the answer directly from Secretary Austin. Austin responded by categorically denying that the military was instructing or in any way embracing CRT.

But before moving on, Democratic Representative Chrissy Houlahan yielded some of her speaking time to General Milley, so that he could deliver the remarks he had failed to squeeze in earlier. Milley gave a little speech, probably rehearsed, about how important it was for white people like himself to read critical race theory to understand the kind of “white rage” that by his description had led to the January 6 Capitol riots. For that Sorkinesque performance, Milley became an instant legend among liberal pundits.

The next evening, Fox News’ Tucker Carlson excoriated Milley on air, accusing him of reading a script for the benefit of his political benefactors. He called the General “obsequious,” a “pig” and “stupid.” Within the span of a few sound bites, Carlson provoked a massive, predictable, and probably intentional backlash.

That very night, on MSNBC, Brian Williams intoned gravely in his signature baritone about “what we’ve just witnessed” on Fox, and invited his guest, retired General Barry McCaffery, to inform the “civilians watching” his program “what they should know” about General Milley. McCaffery heralded Milley’s brilliance, experience and courage, and preached to the choir of MSNBC viewers, “We do have institutional racism baked into America’s DNA.” Williams then showed McCaffery a clip of Fox News’ Laura Ingraham ranting about how Congress should withhold funding from the Pentagon in response to Milley’s testimony, teeing up his many-medaled guest to call Ingraham’s outrage “sheer twaddle.”

Meanwhile, over on Joy Reid’s MSNBC show, a truly remarkable exchange took place. Reid lambasted the Republicans for allegedly calling to “defund the military,” and asked her guest, Rep. Houlahan, who had helped stage manage Milley’s remarks at the hearing, for her opinion on the matter. “When we’re talking about defunding the military,” Houlahan replied to Reid, “our enemies are listening.”

If you’d read a transcript with the names redacted, it could have been a clip of Sean Hannity lambasting Dennis Kucinich after 9/11. But instead, these were spokespersons for the Democratic establishment accusing Republicans who dared threaten to cut military spending of a crime verging on treason. Reid’s social media managers were so proud of the moment, they clipped it and put it out on their Twitter feed.

Lest I be accused of naïveté, I’m well aware of the Democrats’ long record of enthusiastic support for American militarism. But this was something different. This wasn’t the theatrical show of jingoism Democrats are in the habit of performing to blunt the hippie-punching attacks of Republicans. This was pre-emptive. It was heartfelt. It was of a piece with four years of Democratic idolatry for the CIA, the FBI, and the military generals whom partisan Democrats regarded for four years as the thin blue line of internal resistance to the Trump administration’s dictatorial designs. Nor, moreover, were Houlahan’s comments the outcome of some long transformation of thought about the merit of U.S. military hegemony in the world. No new policy, foreign threat, or military action prompted last week’s role reversal between the party of the hawks and the party of the doves. This was pure, unadulterated culture war.

Within the liberal intelligentsia, whatever it is that the phrase “critical race theory” connotes has evolved into a marker of political, emotional and intellectual sophistication, as well as a weapon for summarily writing off the viewpoints of others as thinly veiled bigotry. In turn, resistance to it has become an instrument for ideological mobilization on the right. As with everything these days, this political melodrama has unfolded within the marketplace of social media’s outrage economy. On Twitter and Facebook and TikTok, millions of people line up behind whichever viewpoint most endears them to their friends and followers and the friends and followers they covet.

Last week, this pro-CRT tribalism happened to merge, in one magical moment, with the coalition between anti-Trump liberals and the institutional organs of the government that over the course of the Trump presidency had come into alignment with them — the so-called “‘Deep State.” The outcome was a little orgy of pro-military jingoism among liberals and a conservative tantrum against the Pentagon for pandering to them. The episode had nothing to do with war or geopolitics or foreign policy or defense spending; it was only circumstantially related to the military at all. And it probably won’t last. But it’s an instructive, if ephemeral, example of how the tail of online tribalism now wags the dog of actual, real world politics.

Last week, another thing happened, this one actually consequential: A black former cop all but sealed his victory in the election for New York City mayor. Eric Adams campaigned without apology on a law-and-order platform, and he swept in the most working class, heavily non-white neighborhoods of the outer boroughs.

The progressive candidate in the race, Maya Wiley, whose “community visions” page on her campaign website is a laundry list of statements pandering to each “marginalized” identity group in turn, was endorsed by New York “Squad” members Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Jamaal Bowman, as well as Elizabeth Warren, Gloria Steinem, the Bernie Sanders-aligned group Our Revolution, and celebrity progressive activists Kathy Griffin, Bradley Whitford and Debra Messing. Wiley promised to defund the NYPD by $1 billion, and pitched voters on her identity as a black woman. Yet she drew her base largely from the gentrified belt of Brooklyn and Queens adjacent to the East River waterfront.

New York, like other big cities in the U.S., is experiencing a rising wave of violent crime, after decades of crime rates trending in the other direction. That has posed an obvious challenge to candidates running against the police. But Wiley bet that the tide of post-George Floyd racial justice activism could carry her to victory in a city that was at the center of the national anti-police protest movement.

This is strategic logic that makes sense only to those of us who spend inordinate amounts of our time on the internet. If your political worldview is disproportionately shaped by the sectarian loyalties of the online left and the particular distribution of ideological power and influence found on Twitter, you might assume that the more racially identitarian a non-white candidate is, and the more anti-police their message, the more they will tend to resonate with “voters of color.” You might assume that the candidate who runs on a tough-on-crime platform, aligned, as they appear to be, with the forces of “white supremacy,” would clean up in the white neighborhoods and would be rejected soundly by voters in the “marginalized communities” that they’re so hell bent on oppressing. You would be very wrong.

Poor, non-white people are, without a doubt, the most likely to be victims of police violence and racist discrimination, in part, though not entirely, because their neighborhoods have the highest rates of crime and are thus the most heavily policed. But for the same reason, those same residents are also the most likely to be victims of crime, and despite what white anarchists might tell you about “POC,” most people, white or otherwise, assume that a world with fewer cops is a world with more criminals. Wary as they may be of bad cops, people living in high-crime areas are unlikely to support radical reductions in the presence of police in their neighborhoods at a time when their Citizen apps are sending them push notifications of shootings, muggings and carjackings within a half mile of their home every 30 minutes. This is political common sense, but common sense is in short supply on political Twitter.

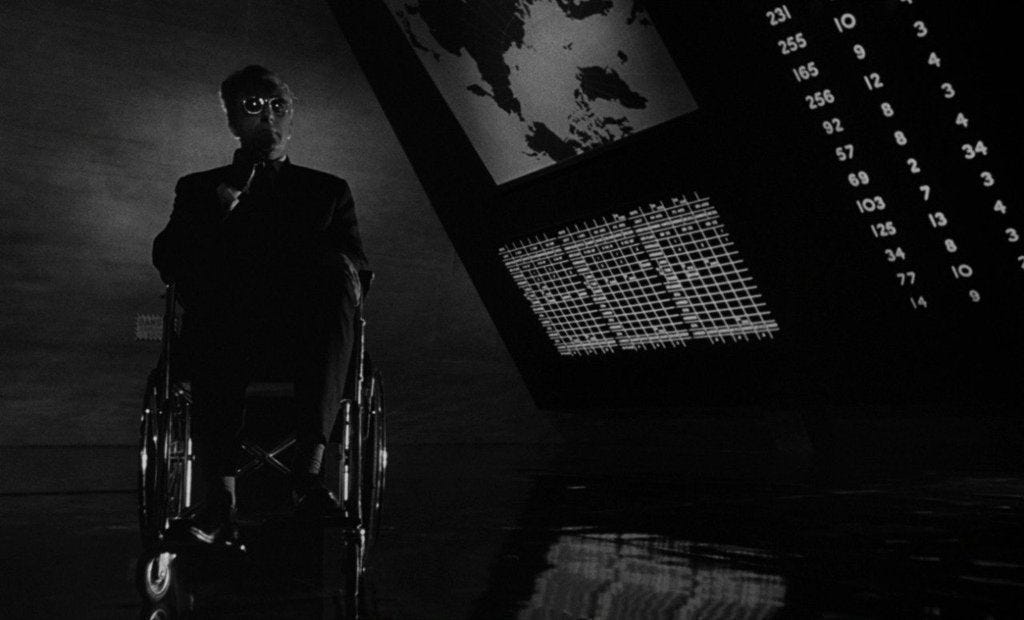

Upon (basically) winning, Eric Adams said, “Social media does not pick a candidate, people on social security pick a candidate.” This is obviously true, as Adams proved. But what social media does do is generate a proxy reality that both reflects and fails to reflect actual reality in unpredictable ways. It’s the shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave. Or it’s The Matrix — whatever; choose your metaphor. It’s a facsimile of the real world. You can choose to live in it, play by its rules and engage in its power struggles, and then, like a video game, you can turn it off and participate in actual society, and, with some effort, perhaps even make some actual social change. Or you can take the blue pill and pretend they’re the same thing. You can rail against cutting defense budgets and lose some more elections, all in the warm, virtual glow of approval of your Twitter followers. For many American leftists today, that seems to be good enough.

About four years ago, I left the world of organized religion. For soooo long, I'd been doing intellectual gymnastics to make the realities of religious life jive with the stated tenets (it took so long because I was raised in it, and as we know, what you learn as a child creates the framework for your whole life. Changing that is hard). One of the gifts of leaving organized religion is now I immediately pay attention to intellectual red flags whenever I'm exploring a new idea or ideology.

For me, when "progressive" activists began to turn conversations in directions I simply couldn't follow, I paid attention to that red flag. I loathe that the terms "identity" and "CRT" have become nearly meaningless catchalls, but I've come to see them as ham-handed objections to actual, legitimate concerns.

Examples:

Activist: white people need to learn.

Same activist, later: it's not my job to teach you; stop asking questions.

Activist: white people need to stand up as allies.

Same activist, later: white people need to do more than just be so-called "allies"

Activist: Robin DiAngleo and white fragility!

Same activist, later: fuck Robin DiAngelo and white fragility!

These are just surface-level examples of ideological pretzels that reveal one of the core issues with CRT and how it's playing out in the public sphere (which is based on lots of other cultural theories of the 60s and 70s), and that is if you follow its tenets to the endpoint, the endpoint is there is no hope. There's no way any of this can be remedied. So instead of working toward policies and celebrating victories that provide material relief to people (healthcare, a living wage, affordable quality childcare, etc.), we're just making pretzels.

Leighton, this piece is the reason why I am exclusively on substack for news and politics now. I spend very little if any time on social media most days and am gladly paying for content from talented writers and cerebral thinkers like yourself that help me connect the dots outside of the ideological world of MSM. I am signing up as a subscriber as soon as I finish typing this note. Well done!