Honey Mahogany: SF's Stock Image Candidate

In San Francisco's drug-ridden SoMa neighborhood, voters will choose between substance and image.

Adjacent to San Francisco’s seedy Tenderloin District is an area called SoMa, which stands for “South of Market.” In the nineteenth century, when Jack London was alive, it was called “South of the Slot” — “the slot” being a track that ran down the center of Market Street, which cable cars ran on before they were destroyed by the 1906 earthquake. This is how London described it in his short story of the same name:

North of the Slot were the theaters, hotels, and shopping district, the banks and the staid, respectable business houses. South of the Slot were the factories, slums, laundries, machine-shops, boiler works, and the abodes of the working class.

Through most of the twentieth century it remained that way, but during the tech boom, the neighborhood, now re-branded as “SoMa,” was upended. Luxury high rises for tech workers sprang up so quickly that when you looked at the San Francisco skyline it was hard to keep track of which skyscrapers had been there the year before. On Market Street, which divides SoMa and the Tenderloin, homeless addicts would stagger around on the sidewalk alongside busybody coders and project managers beelining it from their condos to their office cubicles.

Today, the tech workers are gone. The pandemic and the shift to remote work emptied out the office buildings and gave the coders and project managers yet another reason, on top of the city’s ridiculous cost of living and its intractable blight, to move out of San Francisco. The hustle-bustle of the ballooning digital economy evaporated, and the open air drug market of the Tenderloin seeped over Market Street and filled the vacuum. In the early days of the lockdowns, Shelter-In-Place hotels opened up and the homeless people who were temporarily housed there “used the streets as their living room,” said local deli owner Adam Mesnick, who has documented the deterioration of conditions on the streets on his popular Twitter account. The sidewalks are now occupied by drug dealers armed with guns and machetes. Addicts clog the bus stops and alleyways, passed out or barely conscious. The residents of the new condos who decided to stick around are organizing Neighborhood Watch groups and other self-protection committees, Christian Martin, Executive Director of SoMa West Community Benefit District, told me.

“Swarms of drug dealers. People with body parts missing,” is how Mesnick describes what he sees on SoMa’s streets. “It looks like wartime photos.”

Next month, voters in SoMa will decide whether to keep their current Supervisor, Matt Dorsey, or replace him with his only viable challenger, Honey Mahogany. Their choice will go a long way toward determining how the city manages the chaos on its streets — whether it’s through the prosecutorial approach of the new District Attorney, Brooke Jenkins, or if it’s more like her anti-police predecessor, Chesa Boudin. “We have very little alignment among city Supervisors on how to address the crisis,” said Asheesh Birla, who used to work in the neighborhood and is active in city politics. The election in SoMa will help break the deadlock between ideological progressives and political pragmatists.

Every aspect of that decision is new. Dorsey, a middle aged, white, HIV positive gay man and recovering addict, is the incumbent, but he was appointed by the Mayor just five months ago, after his predecessor won a seat in the State Assembly. Mahogany, a black trans woman who appeared on Rupaul’s Drag Race and who has long been active in various San Francisco Democratic Party clubs, worked for the prior supervisor but has never held formal elected office before. The district itself is new, too: redistricting has severed SoMa from the Tenderloin, making this the first election for District 6 within its new boundaries.

Dorsey has made eradicating the open air drug market the signature issue of his campaign. His program, which he has introduced as a 21-page resolution at the Board of Supervisors, calls for a mix of harm reduction strategies and abstinence-based recovery for drug addicts, arrests and non-carceral monitoring of drug dealers and interdiction of drugs.

Dorsey is a close ally of Jenkins, who was also appointed by the Mayor last May, after the prior DA, the infamously lenient Chesa Boudin, was fired by voters in a recall election. Dorsey used to be the spokesman for the police department, and he has regularly appeared in press conferences and fundraisers alongside Jenkins, drafting off of her towering popularity.

Mahogany, by contrast, is known for her history as a progressive activist. She opposed the recall of Chesa Boudin and has suggested in the past that the Tenderloin didn’t need more police. But she hasn’t emphasized that reputation in her campaign. In a recent debate, her positions on drugs and crime were barely discernible from Dorsey’s. People I’ve spoken to assume the shift is calculated. “She’s following the polling,” said Kanishka Cheng, founder of Together SF Action, a good government group.

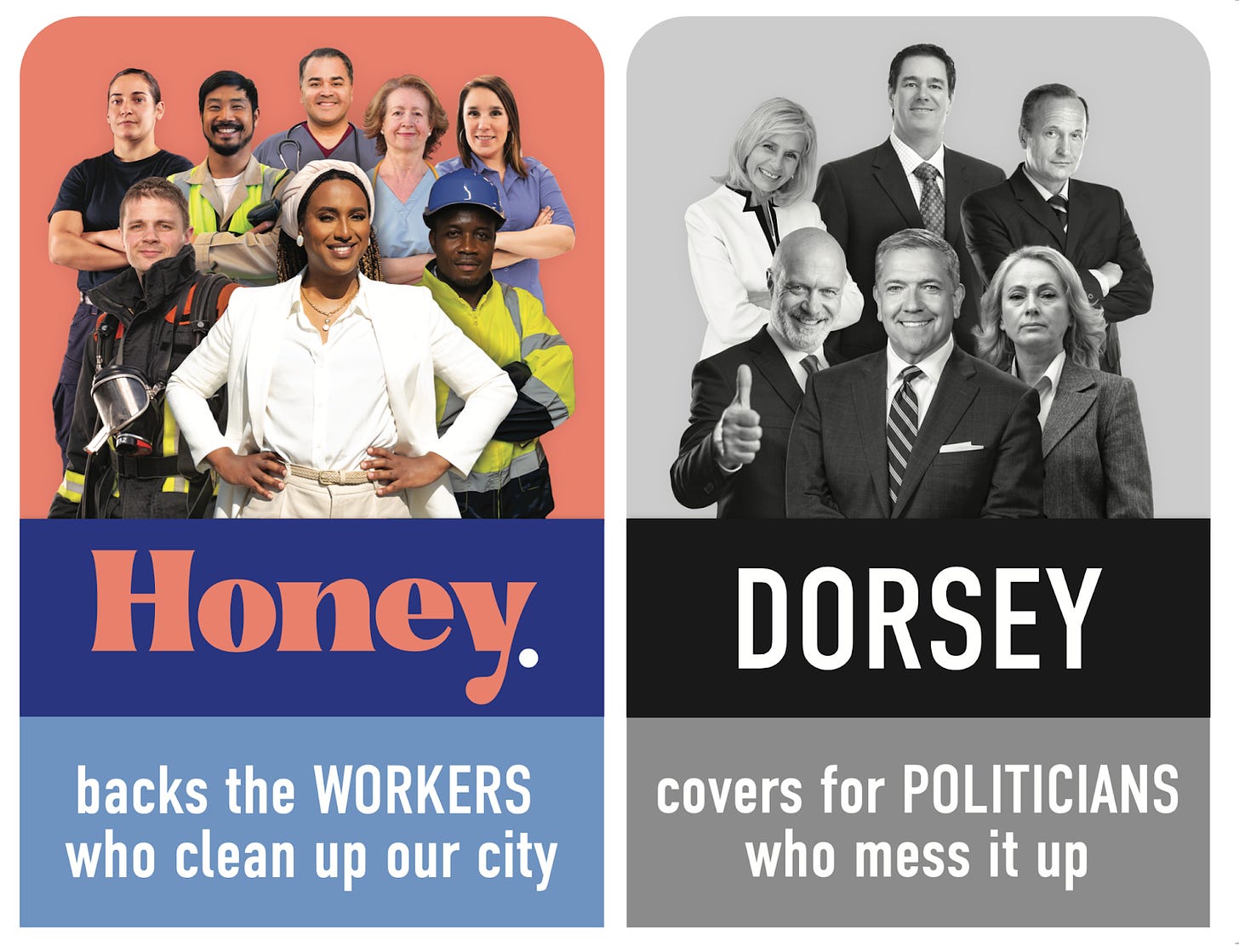

Mahogany’s campaign, in fact, doesn’t seem to be driven by issues at all. Her website has no mention of her policy positions, speaking only of her personal background and endorsements. Her message to voters is her image and her identity. Her latest mailer illustrates it vividly. It features a photo of Honey, in full color, with an array of racially diverse working class people behind her. That image is juxtaposed with a black and white picture of Dorsey with an all-Caucasian ensemble of corporate-looking politicians.

But the people in the images are all fake. A reverse image search shows the actors in each composite photograph are a photoshopped collection of stock images.

Moreover, the fake workers standing behind Honey belie a deep bench of support from the moneyed elite behind Mahogany’s campaign, much of it from outside of California.

In her last campaign finance disclosure, Mahogany received the maximum financial donation from Bradley Barnett, an executive at an Idaho mining corporation; John Blandford, a public affairs executive in Virginia; Nicholas Colina, head of operations at Anco Iron, a construction concern; Corey Eckert of Structure Properties, a major S.F. landlord; and many maxed out donations from employees of major tech companies, such as Facebook, Google and Stripe.

What could be more indicative of the kind of political backscratching she’s trying to pin on Dorsey than maxed-out legal donations from the most powerful business interests not only in the city, but in the country? Or, for that matter, receiving the endorsement of the San Francisco Democratic County Central Committee while personally chairing the organization?

Mahogany’s appeal to image over substance is a cheap and cynical political strategy. It’s one that San Francisco has seen before.

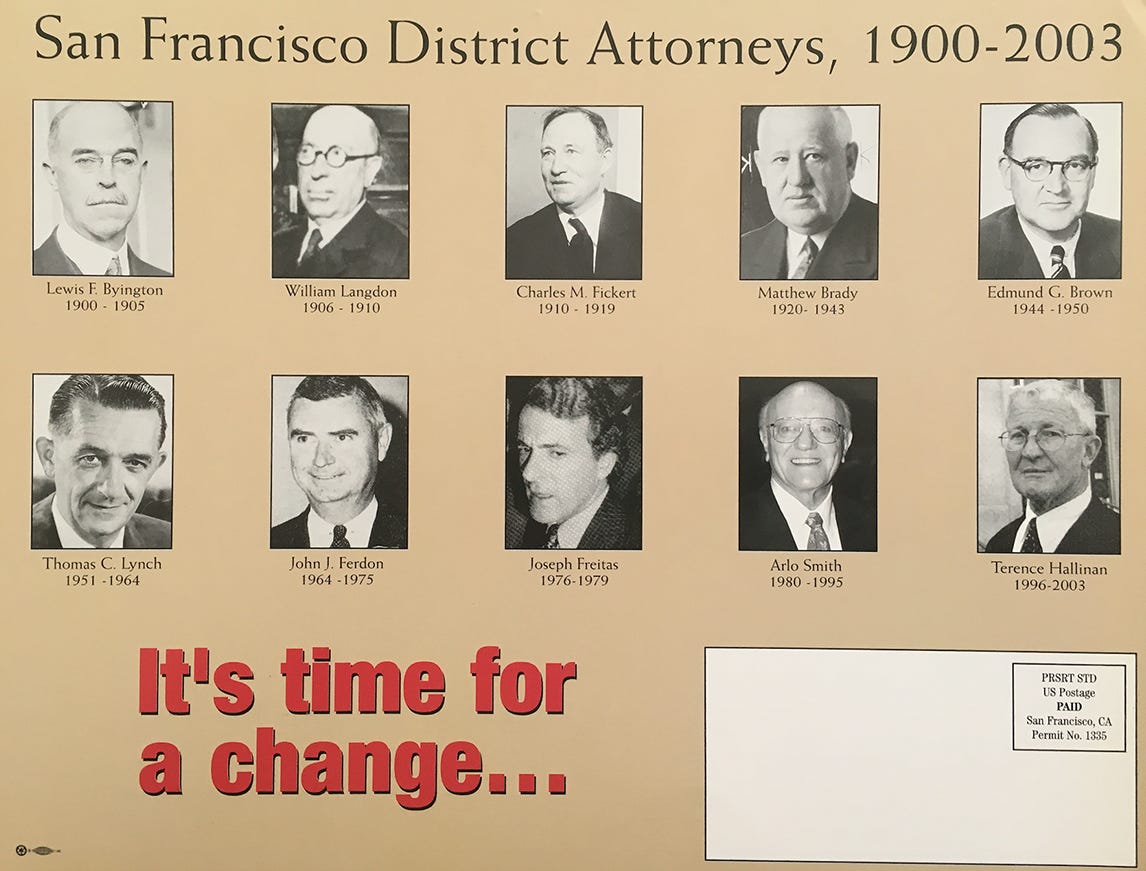

In her first bid for public office, Kamala Harris used the same tactic. In one of her final mailers in the 2003 San Francisco District Attorney race, Harris sent a similar appeal to voters right before the election. It showed a black and white image of all the previous district attorneys, all of whom happened to be white, followed by “It’s time for a change.” No matter that many of those district attorneys, including future Governor Edmund Brown, were progressive reformers who went on to radically improve the lives of Californians.

The message from Harris, like Mahogany today, was simple: forget policy, forget power, forget the actual issues at stake in voters’ lives. Here are some stock images to remind you of racial differences.

Mahogany’s appeal is a particularly awkward fit, moreover, with the current political coalition behind Dorsey. If you replaced those black and white stock images with the actual politicians standing behind Dorsey, first and foremost you would find Mayor London Breed and DA Jenkins. Police chiefs don’t make endorsements, but if they did you’d see SFPD Chief Bill Scott, too. These are not exactly the racial optics Mahogany is contriving.

For voters concerned less about image than about the violent drug bazaar outside their doorsteps, the most significant of Mahogany’s endorsements may be Mano Raju, the Public Defender who has made it his office’s mission to make it impossible for the city to do anything, no matter how mild, to disrupt the cartel-backed drug trade downtown. At every opportunity, Raju calls Jenkins’ approach to drug enforcement a return to the “War on Drugs,” invoking the ugly images of the LAPD Rampart scandal and other civil rights nightmares from the 1990s.

But what people in SoMa who I’ve spoken to are seeing on their streets today is not the dark days of the War on Drugs, but reason to hope for peace and safety in their neighborhood again. Jenkins is working with the police department to step up arrests of drug dealers, and people in District 6 say they can see the difference: the dealers are scarcer and less emboldened, and from time to time you actually see cops detaining people, which simply stopped happening under Boudin.

Mesnick says he sees Dorsey around the neighborhood, riding his bike, talking to people. He refers to the Supervisor’s presence and his nuanced knowledge of the local drug trade as “boots on the ground.” Mesnick knows Mahogany, too, from when she was an aide to Dorsey’s predecessor; he was punted to her a lot when he had complaints. He thinks she’s “a great person,” but describes her approach to the neighborhood’s dystopian conditions as “a lot of excuses, a lot of rhetoric, a lot of ideology.”

Jenkins’ citywide popularity is indicative of voters’ urgent desire for concrete action on the addiction crisis and a radical break from the recent past, not a continuation of the policies of Chesa Boudin. Last month, Jenkins announced that she would consider charging fentanyl dealers whose sales led to fatal overdoses with murder. That decision has the support of 69% of voters in the city.

It’s hard to argue with that kind of support. If voters in D6 see Dorsey’s leadership as integral to Jenkins’ success, an army of stock image actors won’t be able to change their mind.

I live in LA, not SF, but the vibe is similar and we both obviously live under the reign of Social Justice, which makes its believers feel pure & holy even as their policies only make the world around them crumble.

I was driving home a few days ago on Pico Blvd and there is a bum camp there under the 405 overpass. A drugged-out zombie wandered out into traffic and we all had to slam on our brakes and a girl on a bicycle next to me came close to being brained on the bumper of the car in the next lane.

After I stopped cursing, I had 2 thoughts:

1) We have prioritized the lives and needs of a small sliver of society, our most dysfunctional sliver, who have been sculpted into Victim Gods, who can never be questioned or imposed upon. Thus, entire areas must become dangerous and off-limits because doing otherwise would be taboo or "cruel" or in violation of their "rights". (Because their "rights" reign.)

If there had been a major crash and injuries, we would have all ended up in the hospital and the junkie who wandered into the street would have been back in his tent getting high oblivious to the damage and suffering he caused.

2) Whoever made this state/country/city and its laws and courts and infrastructure bestowed upon us the great gift of Civilization and we are in the process of destroying that gift. Cali is in the process of de-civilizing all in the name of worshiping the Victim God.

It is really sad and shameful and someday people will look back at 21st century and see all the gifts we were given and wonder how we squandered them and turned a paradise into a garbage dump.

Great article. The problem in San Francisco is it has a very low and pathetic voter turn out and so many voters are very ill informed. I guarantee they will have no clue that those pics are stock photos. I'll post this on Nextdoor and hopefully it will gain some traction.