Discover more from Social Studies

When Edward Snowden warned that the digital mass surveillance state built by tech corporations and government intelligence agencies amounted to a “turnkey tyranny,” what’s happening right now in Canada is exactly what he meant. Just as armed drones have made waging war as easy as playing a video game, information technology has taken the friction out of building an authoritarian state. It used to be hard to repress people. You’d have instill enough fear or distribute enough patronage to get the police and the military in line with your ambitions; you’d have to actually send the goons out to crack skulls; you’d have to control the judges and set up kangaroo courts to fill your prisons with your political enemies. It was all very ugly and messy and at every point along the way you’d be sure to meet stubborn and potentially violent resistance.

And in fact, Trudeau has sent the goons out to crack a few skulls, but that’s almost parenthetical to the real power the Canadian government is wielding against its citizens: the power to force consent by depriving families of their livelihoods. The Canadian government has directed financial institutions to freeze bank and credit card accounts not only of direct participants in the trucker convoy, but of those who have donated to them. It’s basically an old school starvation siege, but executed digitally instead of physically and with the aim of clearing out a city rather than conquering it. And Trudeau’s government has made clear that it won’t end with the truckers going home.

The power the Canadian government has arrogated to itself is both stupefying and technically easy to do. Per Snowden, that’s what sets this century apart from the last one: radically abridging the civil liberties of entire populations requires no particularly strenuous effort, just an audacious act of will.

In the last century, what’s happening in Canada might have been described as a class war waged from above. That is, it’s a war of the ruling class on an organized and rebellious cadre of the working class. But in 2022, a more useful framework can be found in Martin Gurri’s conception of “the center” versus “the periphery” (actually, Gurri says “the border,” but for reasons I won’t bore you with, I prefer “periphery”). The “center” is the political, economic and cultural establishment, embodied by Justin Trudeau better than anyone in the world. The “periphery” is the anti-establishment riff-raff, organized loosely and spontaneously online, fusing together dissidents of all flavors: left, right, and neither. Occupy Wall Street, the Indignados, the Yellow Vests, the truckers — these are the postindustrial peasant revolts of the periphery.

In its confrontation with the center, the periphery uses instruments its opponent cannot control: the tools of memetic propagation and online mobilization. Culturally, the internet is a flat, decentralized and chaotic place, which bestows an inherent advantage on the anti-establishment public in its campaign of asymmetric warfare against the center. But structurally, the internet is the opposite: it’s a hierarchical, highly centralized and strictly ordered space where attention is channeled through a small number of colossal platforms and money flows through a half dozen giant payment processors. This concentration of power is a potent tool in the hands of the center: to shut down the periphery, it needs only to influence the actions of a handful of actors, each of whom are themselves high profile members in good standing of the establishment. All the center needs to do is apply sufficient political pressure on a few chummy corporate leaders and a rebellion can be suppressed without a single shot fired: much cleaner, safer and aesthetically inoffensive than bringing the full, naked power of the state down on dissidents like it was 1989 in Tiananmen Square.

If the cries of “fascism” by the most energetic critics of “the new normal” sound both histrionic and defensible at the same time, the reason is because most of our historical analogies of autocratic takeovers are from the industrial age. Back then, it took a full scale reordering of the entire economic, political, cultural and social order to achieve top-down control over dissent. But we don’t live in such crude times anymore. Today, we have more refined instruments.

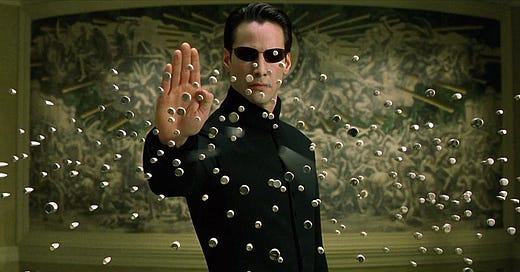

This is what we have to look forward to: surgical authoritarianism. In the twenty-first century, the brute coercive power of the state will not require the construction of a totalitarian apparatus to control our actions and thoughts at all times in all places, as it did in the last one. In normal times, dissent will be happily tolerated. But when the state feels truly threatened, it will merely log into the operating system of our digital society, switch to God Mode, hit a few keystrokes and nuke its opposition.

Cosmetic pluralism, freedom and democracy in times of peace, and targeted, draconian exercises of suppression in times of crisis: this is the kind of bespoke authoritarianism our technological age has made possible. Empty, performative dissent can be not just allowed but celebrated, while real public revolt is destroyed as cleanly, summarily and discretely as in a drone strike. The turnkey can be turned on and off and on again, depending on the risk threat. It’s a more calibrated, frictionless, user-friendly form of control. It works not in the foreground but in the background. It’s just part of the operating system. You might not even notice it.

Subscribe to Social Studies

Politics, media and social theory

I am by temperament resistant to authority, but am still left stunned by how little time it took to start building a better genocide.

An ex-Noo Yawkuh, I now live in a very blue community in a mostly libertarian state, and my younger self would have been shocked to find me grateful to have a Republican governor and developing, for the first time in my life, an appreciation for the 2nd Amendment. (Though such attestations should never be necessary, I voted for Obama twice-yes-twice, voted affirmatively for "none of the above" in 2016 and skipped 2020 altogether.)

I chose not to get vaxxed against the current Plague not out of any philosophical, religious (I ain't got no dogma) or political impetus, but for rational reasons--this thing ain't been tested long enough; dissenting scientists have been ruthlessly suppressed, which any normal person would find concerning; I've never gotten a flu shot either and consider this the same category of risk (I got the flu on my 30th birthday, lo these many decades ago, and it was a brutal week but illness gets ya like that sometimes. It's not the Crawling Eye, or something.)

And the reaction to people like me, in letters to the editor in our regional paper (where I was just one of two-count 'em two people to rationally lay out our reasons) would have made Goebbels proud. The paper's circulation encompasses two college towns and by God the intelligentsia have better pitchforks than the peasantry could dream of.

Leighton, you're one of the best essayists on meaningful subjects I've encountered. Live long and prosper.

This is not a drill. This is the real deal, and we acquiesce at our great peril.

I remember considerable emphasis in my formal education on how important it is to resist these sorts of totalitarian movements. I remember watching The Wave, the Stanford Prison Experiment documentary, the Milgram Experiments, etc. I remember reading about how the Nazis were enabled by people who remained quiet. I remember learning the dangers of group think and scapegoating. We learned how important it was to think critically and question authority.

But throughout it all, the threats were coded mostly as right-wing, at least in my Seattle schooling. I don't remember being introduced to, say, Solzhenitsyn. Through the simple trick of putting a leftist mask on totalitarianism and coding resistance as "right wing," "far right," "racist," "white supremacist," etc., almost all of my educated leftist friends and family eagerly abandoned the principles we were raised with and jumped right on the authoritarian bandwagon. It is so crude and obvious a trick, but the intelligentsia are either oblivious or willfully blind to the evil they are perpetuating.

Particularly with the advent of bank account freezing, not to mention the social and career costs of resisting, this adage has a lot of explanatory power these days:

"It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

― Upton Sinclair, I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked