Social media power struggles matter. I wish that weren’t the case. But we live in a world in which the social media platforms have warped the incentive structures of just about every field of cultural production. It’s naive to think that all the dumb clout wars waged endlessly on Twitter and Facebook don’t have profound spillover effects in the real world. They’ve already all but ruined the profession of journalism.

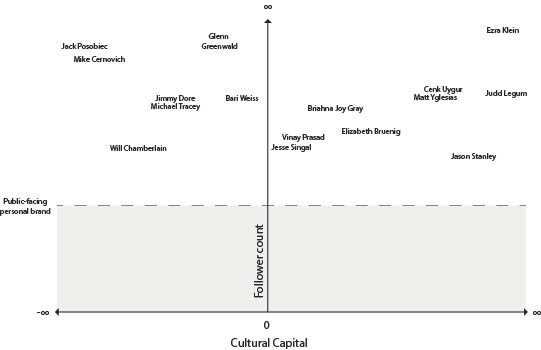

It thus seems worthwhile to try to better understand how those power struggles work. Here’s my attempt to do so, by way of Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital.

Bourdieu conceived of struggles for power in the real world as principally contests over economic and cultural capital. Rival factions of the elite class compete with one another not just over how much of each form of capital they can amass, but also over how much valuation one form of capital should be accorded versus the other. Those who are wealthy in cultural capital but less so in economic capital, for instance, are the most insistent that educational credentials, tastes, manners and other markers of cultural distinction should count for more than mere material affluence as determinants of social status and power. Such an outcome favors their competitive advantage in cultural capital and hedges against their relative deficit of material wealth.

In online power struggles, however, the dynamic is a bit different. Your level of material wealth is mostly a non-factor in the competition for internet clout. If you’re not famous, nobody online has any idea how much money you make in the first place. If you’re a blue check pundit with high name recognition, then most people probably assume you’re some unspecified level of upper middle class and don’t think about it much beyond that. The nuanced markers of distinction between one intermediate tier of affluence and the next, which drive so many status struggles in the real world, are basically invisible in the digital space.

What is highly visible and matters a great deal, however, is your follower count. Like economic wealth in the analog world, it’s sort of a baseline determinant of which broad social tier you inhabit on a given platform, which in turn determines who you’re in competition with and who you’re not. If you have 500 followers on Twitter competing in a different game than those who have 500,000, and everyone knows it. That’s just how it is.

That doesn’t mean that the competition on social media is over follower counts, though. People may be vaguely conscious of how many followers they have versus those with whom they interact online (again, I suspect most people think of this in terms of broad tiers, and aren’t paying attention to differences of a few dozen or even a few hundred followers between one interlocutor and the next), but followers are not a finite resource. Nobody, to my knowledge, is trying to steal anyone else’s followers away from them and add them to their own.

The competition is along the other axis: cultural capital. When it comes to political Twitter (I’ll stick to Twitter here since it’s the platform I know best and also the one where this status competition is the most brazen), there’s a very specific kind of cultural capital that predominates: the specialized language and esoteric knowledge of wokeness. As I’ve noted before, exhibiting your familiarity with and fierce commitment to the political sensibilities of elite four-year college-educated urban professionals today serves the same function that driving a Lexus with a Stanford bumper sticker did in the pre-internet days: it indicates your elevated class position and thus your rightful place on the status hierarchy. This is what I’ve called “moral capital.”

Like its economic counterpart, moral capital is subject to inflation: the more of it that’s out there in the aggregate, the less each unit of it is worth. A few years ago, putting your pronouns in your Twitter bio marked you as a a member of the progressive avant-garde. Then everyone started doing it. Now it indicates nothing other than that you probably voted for Biden. If you want to distinguish yourself as part of the political intelligentsia today, you have to go further than that: perhaps by adopting a non-binary identity, or by opening every Zoom meeting with a land acknowledgement. Once those practices go mainstream, they’ll have to be replaced with something else.

Claiming and defending one’s place in the class status order thus depends upon constantly showcasing one’s moral capital (simply put, virtue signaling), while staying closely enough attuned to the evolution of the broader social justice discourse to be among the earliest adopters of every new belief, turn of phrase, affectation or neologism before it reaches the point of cultural saturation at which it no longer distinguishes you as part of the moral and political elect. Reading the right authors and following the right influencers is a critical part of maintaining this edge.

Outside of the rarified circle of high follower, high moral capital progressive blue check Twitter, the true nature of this status competition is obvious. Indeed, more or less the only people who don’t readily recognize it for what it is are the blue check participants themselves, whose entire self-conception depends upon maintaining the illusion that their online displays of moral conviction are a reflection of authentically held beliefs (Bourdieu calls this willful delusion the “doxa” of the field). They constitute a tiny minority, however, of those on Twitter and every other online platform. Relative to them, the vast majority of users are low in either follower counts, or moral capital, or both.

Among the low follower accounts, there are a couple different ways to participate in the Twitter game, depending on one’s aspirations. Some “lowbies” strive for larger followings and for credibility from the blue check crowd. These people tend to buy at least somewhat into the blue check doxa. They spend much of their time on Twitter lining up in support of favored blue checks and against those blue checks’ rivals. They’re occasionally awarded for their loyalty with a blue check retweet and with the handful of new followers that might come with it.

Others seek to level the playing field by exposing the obvious fraudulence at the heart of the entire blue check discourse. They tend to adopt an affectation of bemused pessimism, which I suspect often (but not always) conceals a simmering cauldron of frustration. These are the anons, trolls and reply guys who constantly torment the blue checks with varying levels of success. For the most part, the blue checks can safely ignore these users, but not entirely: there’s a small but ever-present chance that a dunk could go viral, causing real reputational harm.

Then there are the low moral capital users. This includes “normie” Twitter users who have not opted into the woke discourse and are indifferent to the status competition around it. These are, effectively, non-participants in the Twitter game. Mostly lurkers.

It also includes ideological conservatives who inhabit a Twitter universe in which the moral capital economy of progressive Twitter is turned upside down, its reward and penalty structure reversed (in the graph above I represent this as negative moral capital). It’s important to note, however, that conservative Twitter does not represent an equal and opposite inversion of progressive Twitter. Progressive ideology is hegemonic on the platform; conservative Twitter is shaped entirely in reaction to it and has no independent existence from it. High-profile, blue check conservatives on Twitter have the same incentives as the trolls: they gain status by causing reputational harm to the priestly caste of progressive blue check Twitter. The difference is that they’re operating at scale: careers and fortunes can be built by “owning the libs.”

The real world impact of all of this is utterly toxic, and not just because it polarizes our politics. Even though status competition on liberal Twitter is carried out under the banner of “progressive politics,” the dynamic it establishes is utterly antithetical to mass movement building. The prize of the contest, after all, is social exclusivity. Allowing more people into the fold is inimical to this objective. The more “mass” the “movement” becomes, the less membership within it serves as a rarified social status marker. The phenomenon thus leads in the opposite direction: toward a politics based on ever more unattainable levels of personal moral purity and more and more culturally inaccessible, avant-garde expressions of it. This is the opposite of populism: it’s elitism. It’s practically designed to alienate the masses in order to elevate the privileged progressive vanguard above them.

Worse, the competition for moral distinction warps our very understanding of reality by prompting the formation of novel, rarified political and even empirical beliefs that can be wielded as status signifiers — what Rob Henderson calls “luxury beliefs.” In order to stay at the cutting edge of the PMC intelligentsia, status competitors are forced to contrive ever more radical-sounding slogans and then compete to prove their loyalty to the new dogma. “Abolish ICE,” “Defund the police” and “Trans women are women” are all tenets of the progressive faith that followed this trajectory: they began as ostentatious expressions of political defiance that served as edgelord status signifiers on Twitter, then were hardened by the dynamics described above into more or less mainstream political tenets of the progressive activist world, and then, especially in the last case, became literal beliefs about the world around us. This is just one of many ways in which social media platforms are warping and supplanting traditional fields of knowledge production, including science itself.

From the outside, all the endless squabbling on social media may look frivolous — and it is. But it’s no less insidious for it. Increasingly, the online platforms are not mere diversions from the “real world”; they are the real world. The political debates on cable news and in Congress are shaped by their discourses. The agendas of activists who influence the decisions of your local elected officials are informed by them. The judgments of scientists, medical professionals, and public health and safety officials are influenced by the consensuses formed by liberal blue check Twitter, which harden overnight into conventional wisdom. The fulcrum of our debates around public policy is thus shifting away from the standard of scientific verifiability or even political popularity, and toward that of intra-class status competition within the PMC. And that way madness lies.

In a way, Twitter is like shady lobbying entities. Most people who have never been on the site don't realise how much it touches their lives.

I have a really hard time with Twitter. I started on the platform in ‘07 to mostly promote a board game I was developing. I also had an account specifically for news and info trained on finance accounts for my job at an HFT. Around 2015, I finally abandoned all of my accounts as completely useless, uninformative and un-fun.

Many important and smart people that I respect have come up with arguments about why Twitter matters and why I should care. But I’m just not seeing it. Is the value of Twitter, say Network effect or historical record, such that something else couldn’t be substituted? Are the problems with Twitter technological, ideological or deeply ingrained in what humans are? Is it more than a fad, or the fad of fads?

From my perspective, it’s just another dumb thing the masses have convinced themselves means something but actually means nothing. If Twitter disappeared tomorrow what would we actually miss? What important contributions would we talk about?

I just can’t see why I should put any effort into Twitter (or any Clout game, for that matter) aside from my own ego and that’s a problem I solved decades ago: what I think simply doesn’t matter.