Chesa Boudin's Legacy of Failure

San Francisco voters didn't fail the progressive movement. Progressives failed San Francisco.

In 2019, I co-produced a campaign ad for now-former San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin. It was a good ad. I’m still proud of it.

My filmmaking partner and I made the spot practically for free. We believed in Boudin’s decarceration message and wanted him to advance a national movement for criminal justice reform by demonstrating that having compassion for offenders and ensuring public safety were not mutually exclusive goals. In San Francisco, Chesa would prove that we can have both.

I still believe that message. But that’s not what Boudin proved at all. In fact, his tenure as DA demonstrated exactly the opposite.

Shortly before the June 7 recall election that kicked Boudin out of office, Ross Barkan wrote a screed for New York Magazine that reflects precisely the progressive mentality that ensured political doom for Boudin and the movement around him. Barkan’s basic argument is that San Francisco, ackchyually, isn’t that progressive at all. The city “lacks a working-class population that could buoy progressive candidates,” Barkan claims, and is instead dominated by the billionaires and tech bros for whom, he mind reads, “homelessness is more an aesthetic annoyance than a humanitarian catastrophe.”

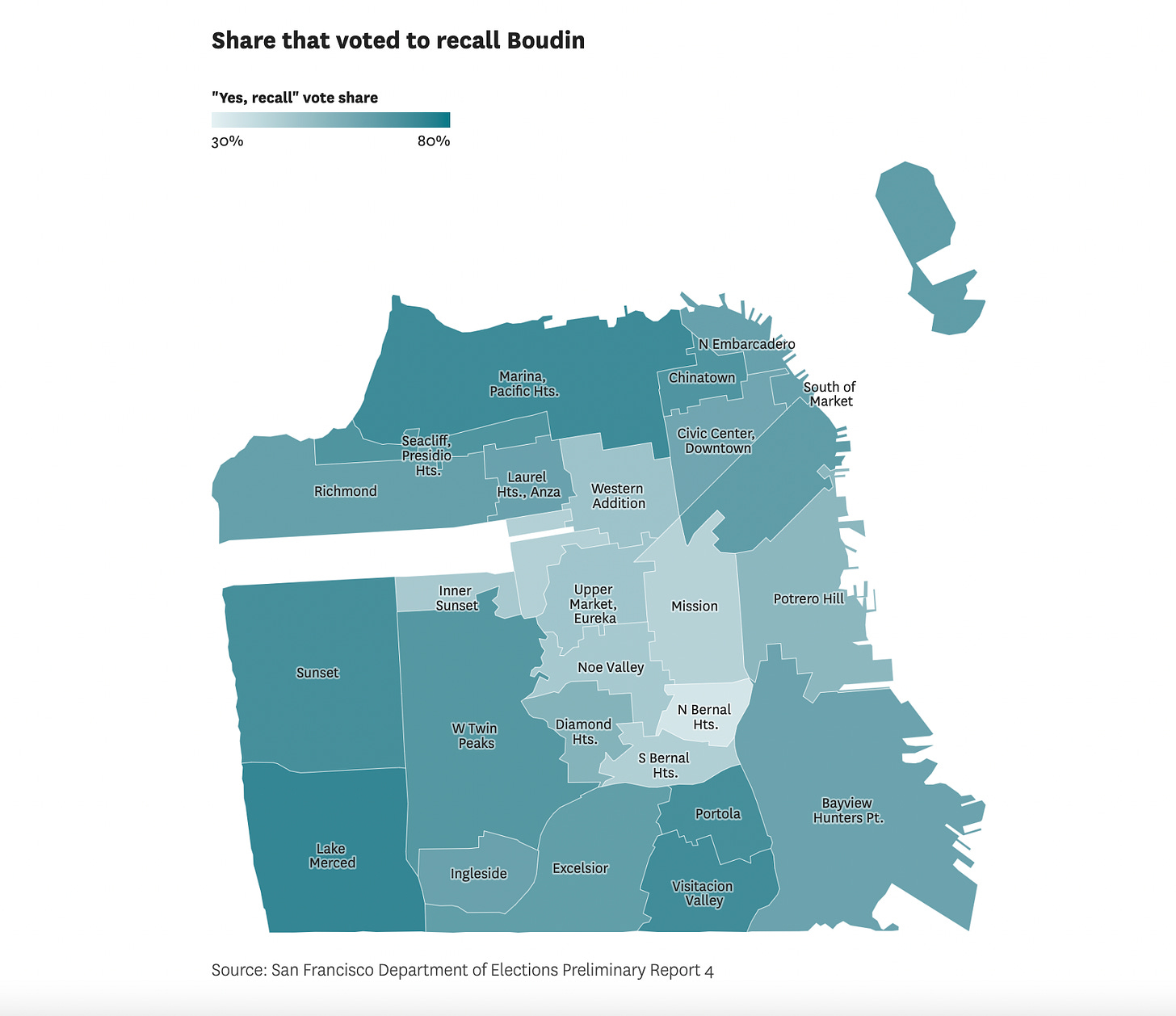

Barkan lives thousands of miles away, in New York City, which you can tell from his basic ignorance of San Francisco’s politics, evidenced plainly in the correction the magazine had to issue for the reporter’s misidentification of former Mayor Frank Jordan as a Republican. His biggest blind spot, though, is one he shares with progressives everywhere: the assumption that working class voters are by definition “progressive” in the first place, rather than constituents who need to be won over to the progressive cause. In fact, the landslide vote to recall Boudin came lopsidedly from middle- and working-class neighborhoods all over the city, while the bastions of Boudin’s support were among the whitest, most affluent districts. Bayview Hunter’s Point, the poorest, most dangerous neighborhood in the city, voted to recall Boudin by 62 percent, while a majority of voters in tony Noe Valley voted to keep him. As a New Yorker, Barkan should have anticipated this result, since it’s the exact same pattern that got the blue collar law-and-order candidate Eric Adams elected Mayor of his own city.

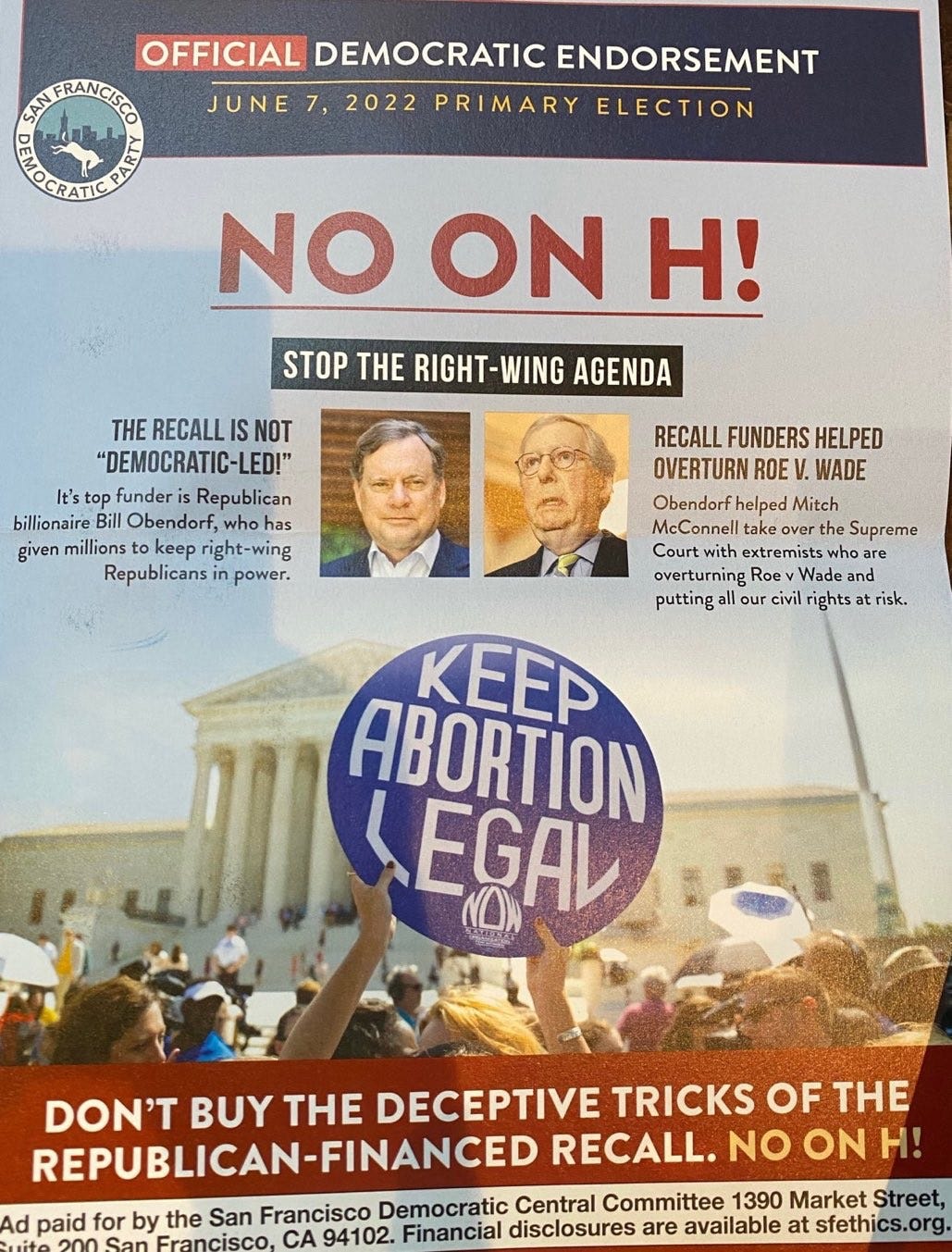

The same assumption fueled the failed messaging of Boudin’s own anti-recall effort. The No on H campaign hinged on a single claim: that the recall effort was a right-wing power grab financed by malevolent oligarchs. It’s a message that undoubtedly played well with Chesa’s supporters, flattering as it was to their self-conception as the true “progressives” defending the poor and powerless from the corrupt ruling class. But it flew in the face of what ordinary voters in San Francisco had been seeing every day, all over the city, for months: pro-recall campaign tables in front of grocery stores and at farmer’s markets manned by septuagenarian Chinese grandmas who spoke in heavily accented, broken English. Clearly, the energy behind the recall effort was not coming from anti-choice (???), Mitch McConnell-supporting conservative activists, as one campaign flyer absurdly insinuated, or by Barkan’s reviled tech bros.

Instead, the grassroots support for the recall was driven by exactly who it appeared to be driven by: ordinary San Franciscans who were unhappy with the city’s growing lawlessness.

As the progressive movement has become increasingly a movement of the professional managerial elite, it has become easier and easier for its activists to adopt slogans that sound morally bold and politically radical because their real world consequences are suffered by others. A decade ago, progressive activists wouldn’t have had the luxury to call for abolishing the police, because their own constituents were among those who would be forced to live with the fallout of surging crime rates in low income neighborhoods. They had to actually take those people’s concerns seriously, as they were a critical part of their movement. Today, those working class constituencies can be safely ignored, even as college-educated radicals claim to speak in their name. Your local DSA chapter has to make space for the political posturing of the Ivy League-educated lefty lawyers who attend its meetings and run for its offices, but not for the Yemeni liquor store owner in the Tenderloin who has never heard of “praxis” or “settler-colonialism” but has to carry a sidearm because he’s been robbed at gunpoint twice already. It’s the former constituency that supported Boudin’s agenda. Contra Barkan, it’s the latter one that voted for the recall.

Working class San Franciscans, like middle class and upper class San Franciscans, wanted Boudin out because they were tired of having their cars broken into, of having to worry about being jacked up on the street in broad daylight, and of having their local retailers shuttering and cutting back hours because of an epidemic of shoplifting. And they were also concerned about the “aesthetic annoyance” of tent encampments and open air drug markets, even while recognizing it as a “humanitarian catastrophe.” It’s as unclear to me why Barkan can’t conceive of it being both as it is that he thinks there’s something reactionary about not wanting to walk your kids to school past people smoking meth and sticking needles in their arms — a blight that plagues the poor immigrant families that live in the Tenderloin, not the richies in Pacific Heights.

Barkan also seems happy to just take Boudin’s explanation at face value that the DA has no responsibility over homelessness, an issue that has, in Boudin’s words, been “dishonestly foisted onto my office and onto me” by the recall supporters. That’s a preposterous claim. The homelessness issue, especially in the Tenderloin, is an addiction crisis, and Boudin made the explicit decision not to bust street level drug dealers. Boudin could have had the intellectual integrity to defend that decision on its merits, explaining how his policy of allowing the open air drug markets to thrive was somehow worth the trade-offs, but instead, as usual, he evaded responsibility altogether to the friendly reporters who were happy to let him get away with it and who were thus the only ones he would ever allow to interview him.

But gaslighting voters into letting you off the hook is not the way to make real social change. It’s not enough just to win political power and ram through all the radical promises you made on the campaign trail, whatever the result. You have to actually govern. That means you have to implement your reform agenda in a way that mitigates its adverse impacts, and build a system that upholds your principles while making life better, or at least not worse, for your constituents. You do that, and you build a popular model that can endure and be imitated throughout the country. You fail to do that, and you discredit your vision as a realistic political project and ensure that nobody ever follows your doomed example again. You actually set back your cause, perhaps for a generation. That’s what Chesa did.

“If Boudin loses,” Barkan wrote, “the criminal-justice-reform movement in San Francisco and across America could be dealt a grievous blow, at least in the short term.” Well, Boudin did lose. And the criminal justice reform movement was indeed dealt a grievous blow, and probably not just for the short term. But that’s not because those sneaky oligarch puppet masters will be “emboldened,” as Barkan insists. It’s because Boudin said he would deliver on a vision and then demonstrated to voters, through the chaos and destruction that his policies created, that that vision was either a pipe dream or a Faustian bargain.

That’s the lesson Boudin taught to the country even if it’s not in fact true: the problem, in my opinion, wasn’t with Boudin’s vision, which is still a viable political aspiration, but with the incompetence of his leadership. But in politics, good luck with the “real communism has never been tried” defense. In the real world, political failure means ideological failure. And that’s Boudin’s legacy. San Francisco voters didn’t fail the progressive movement, as Barkan would somehow have you believe. The progressive movement was given a chance by the voters, and it failed them spectacularly. That’s a shame, and it’s Boudin’s own shame to bear.

So, you didn't think he was going to do what he actually said he was going to do?! People say there is a fine line between co-dependancy/enabling and empowerment but I don't really think there is at all. When consequences are removed it's enabling. When consequences are clear and fair and society helps the person dealing with the consequences to accept them and see a place for themselves in society when and if they choose to become healthy it's not.

Maybe next time you won't be fooled. Also, may want to check yourself for co-dependant inclination. Not saying this to judge. I came from a dysfunctional family and had some myself. Taking account and accepting my well intentioned but dysfunctional role helped me to move past it to better relationshps.

As a former Cali resident, Chesa and people like him are so obviously wrong I find it hard to believe anyone could fall for their schtick without unexamined personal issues themselves.

I like your articles because they make me think. I can see how Boudin's initial message would be attractive. I also think we have an incarceration problem, and if I found myself or someone I loved on the wrong side of the law, I'd like to think that the system wasn't there just to be punitive. In fact, you're right in a lot of what you say, including that Boudin set back such sentiment by decades.

The problem in this country is that we have all been taught to think in exclusive and exhaustive dichotomies. I've seen such sentiment in some of the comments. And maybe there's a reason. Maybe even though some of us have hope that at some point someone will break the "exclusive and exhaustive dichotomies," it never happens. Our politicians can never seem to "thread the needle," and so we begin to think it can't be threaded. Based on that, we find foolish anyone who suggests it can.

American workers are not the natural base of progressives. They might be the natural base of communists or even socialists (systems that elevate workers). And in a very surprising twist of events, they have become the base of the Republican party, which blows my mind, but there you have it. And this is something you can easily conclude if you study people. America does not have the best social welfare system, but it has a decent one. You can live most places in this country and not work, and many do. And then you throw in places where you can break the law for a living, and you can avoid traditional work and live, I won't say "well," but you can live "as well" as someone who works retail or service jobs, and maybe better.

And therein lies the problem for people like Ross Barkan. They are trying to force into one coalition two types of people: (1) those who believe, still, that work is honorable and/or a way to get ahead and that the system will reward them at some point or that it's inescapable or that they owe it to all those around them to abide by the system even if it's broken, and (2) those that have turned their backs on the system and feel justified in at the least not supporting it with their labor or, often, preying on those who still subscribe to the system (your shopkeeper). This is merely an observation, not a judgment or defense of either group.

But here is the problem, for the progressives and the Democrats, in forcing them to coexist in one party. They can't, not the way the Democrats and progressives have been doing it. And I don't know if people like Ross Barkan realize this and are coldly cynical or if they are naive, but it ends the same. They end up catering to group 2 because that's the group you can't "bully" into submission. At the same time, they either ignore or try to shame group 1 into falling in line. That only lasts for so long, and then you get, well, Boudin's recall and the strange phenomenon of pitting the intellectuals against the workers on behalf of those that, for whatever reason, by choice or by circumstance (like addiction), live outside of and defy the system.

Of course, there's more to the whole thing than what I've described above, and we could "thread the needle" if certain groups were more interested in helping than winning. But if the Democrats and progressives don't stop blaming Republicans and the "ignorance/selfishness/anti-intellectualism/populist sentiment" of the working class, they are going to keep having Boudin moments.