Discover more from Social Studies

Black Culture Matters

But it has nothing to do with biological "race," and everything to do with American history.

Last summer, I wrote a story for Bari Weiss’ Substack on the crime wave in Oakland, the city I live in. I interviewed a violence interruptor named Antoine Towers, and was surprised by his opinion of what was at the root of the crime surge. For some reason I had always assumed that endemic urban violence was mostly a consequence of organized crime, like it is in The Wire. That’s probably indeed the case for a significant proportion of shootings and homicides in American cities, but Towers didn’t see that as the main issue. He saw the problem as random personal interactions that go the wrong way.

Because Covid had kept so many people home from their jobs, he explained, there was just a lot more social interaction going on all day, every day. That meant more instances of interpersonal conflict, and in low-income neighborhoods in Oakland, interpersonal conflict can often lead to gunplay. The way Towers explained it was that two people would get into an argument, and while heads were still hot, they might go back to their cars and get their guns, just in case, because you never know what the other guy might try next. So now you have two people in a heated conflict, and they’re both armed. You can imagine various scenarios of how this plays out.

For most of my life I’ve been a political leftist. That’s inclined me toward wanting to come up with materialist explanations for almost everything, which is sort of the intellectual tradition of the Left. The Left doesn’t tend to gravitate toward cultural explanations of social problems like crime, poverty and violence, probably in part because of the long history of both liberals and conservatives using cultural arguments to — allegedly — blame the victim. If you talk about “black culture” creating criminality, you might be accused of perpetuating racism. (As a believer in the theory of racecraft, I might not disagree with that characterization.)

But that’s only because attaching culture to biological race is, almost by definition, a racist proposition from the very start. I happen to believe that race is fake (a post for another time), but even setting that aside, it assuredly has nothing but a contingent connection to culture. People associated with various races can, and do, share in multiple cultures at once: I’m a mixed-race, middle-class, educated Californian. The cultures that have shaped me are, by pedigree, English, American, Anglo-American, Protestant, Californian, and Japanese, and by osmosis, Hispanic (which comes from being Californian), Yankee (by my ancestors on my father’s side and by my parents’ and my own higher education), African-American (via popular culture in my youth), and probably a half dozen other cultures I could justify if I tried. Some of those are tangentially connected to my biological heritage; most derive from the geography of my birth or the history of my direct ancestors.

But it’s facile to leap from the defensible idea that it’s racist to attribute a particular culture to one’s genetic constitution to the outlandish idea that culture is irrelevant to explaining any social problem. The reality is that there is such a thing as “street culture,” which I provocatively called “black culture” in this headline for the purpose of generating clicks, but which is actually only “black” by historical accident. Genealogically, it’s not “black” culture at all: it’s Scotch-Irish culture.

I just finished reading Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America, by David Hackett Fischer. It’s a tome of a colonial history written back in the 1980s. It’s a remarkable book. Its thesis is, in short, that America’s enduring political culture was shaped by the ancient and distinctive cultures of the respective populations of four regions of Great Britain, which were, respectively, the sources of each of four great migrations to the American colonies. First there was the migration of the East Anglian Puritans to Massachusetts, then the gentlemen cavaliers of the south and west of England to Virginia, then the Quakers of the English Midlands to Pennsylvania, and finally the Scotch-Irish and North English ruffians to the Appalachian backcountry.

It’s the last group that interests me most for the purposes of this discussion (and which interests me most in general).

The region from which this group hailed was the English “borderlands,” which, as I just learned from Google, is also sometimes called “The Debatable Land,” which is an even cooler name. It’s the region that fuzzily separates England from Scotland, adjacent to Northern Ireland (at a time when it was easier to travel by sea than by land, waterways often adjoined regions rather than separated them).

For centuries, this region was a veritable anarchic zone, something close to Hobbes’ and Locke’s “state of nature.” It was the site of almost constant warfare, as the English and Scottish crowns perpetually attempted to conquer it from one another and from the inhabitants themselves, who resisted both. Everything about the culture of the people of the borderlands, down to their style of architecture — simple log cabins that could be rebuilt easily and cheaply if razed — reflected this condition of pervasive violence.

That included this culture’s conception of justice. In a region without a functioning state, order was maintained by the threat of violent retaliation. Your family’s physical security depended upon the assurance that if attacked, you would respond in kind. This material condition of informal deterrence was expressed culturally in the ethic of personal honor. As a matter of self-preservation, one’s reputation for being willing to go to battle over any perceived assertion of dominance by an outside party was paramount. Your life literally depended on it.

On the northern borderlands, allied families coalesced into clans, which were essentially self-defense networks. The clan became the vessel of one’s honor — the medieval equivalent of a personal brand. (My own family is descended in part from the Wallace clan of Scotland.)

All of this, right down to the log cabins, was brought to America with the migration of the Scotch-Irish to the Appalachian backcountry in the eighteenth century. The infamous, generations-long feud between the Hatfields and McCoys of West Virginia and Kentucky, to take just one example, was nothing more than a North British clan war over personal honor transplanted onto American soil.

It’s hard to conceive today of just how violent this culture was. Fischer describes a “sport” brought from the borderlands to the backcountry called “rough and tumble”, in this case between a combatant from Kentucky and another from West Virginia:

The two men entered the ring, and a few ordinary blows were exchanged in a tentative manner. Then suddenly the Virginian “contracted his whole form, drew his arms to his face,” and “pitched himself into the bosom of his opponent,” sinking his sharpened fingernails into the Kentuckian’s head. “The Virginian,” we are told, “never lost his hold . . . fixing his claws in his hair and his thumbs on his eyes, [he] gave them a start from the sockets. The sufferer roared aloud, but uttered no complaint.” Even after the eyes were gouged out, the struggle continued. The Virginian fastened his teeth on the Kentuckian’s nose and bit it in two pieces. Then he tore off the Kentuckian’s ears. At last, the “Kentuckian, deprived of eyes, ears and nose, gave in.” The victor, himself maimed and bleeding, was “chaired round the grounds,” to the cheers of the crowd.

This kind of ritual violence was so endemic in the Appalachians that Virginia state legislators eventually passed a statute against maiming, including “gouging, plucking or putting out an eye, biting, kicking or stomping.”

This gruesome scene was in every way a folk culture of the American South, but it was the farthest thing from the gentile culture of the patrician plantation owners who had migrated from the South and West of England, whose sense of personal honor was invested in noble titles and social rank, rather than a personal willingness to go mad dog on anyone who disrespected you. The Scotch-Irish culture wasn’t the culture of the Southern aristocracy; it was the culture of the rural proletariat — those who later became known as “poor white trash.”

The pejoratives we still apply to their descendants today — “rednecks,” or, a little more antiquated, “crackers” — were in usage even before the eighteenth century. In fact they were brought over from the borderlands of North Britain. If Fischer is correct, “redneck” did not derive from the sunburnt necks of agricultural workers, as is commonly believed, or the red bandanas worn around the necks of striking coal miners in the 1920s. “It had long been a slang word for religious dissenters in the north of England,” according to Fischer, and, in the mountains of the American South, was a reference to Presbyterians. Likewise, “cracker” was a term from North Britain referring to “a low and vulgar braggart.”

Through the nineteenth century, the spread of the rednecks across the advancing American frontier brought their Scotch-Irish borderlands culture to a huge swathe of the continent. In Fischer’s words:

The borderers were a restless people who carried their migratory ways from Britain to America . . . The history of these people was a long set of removals — from England to Scotland, from Scotland to Ireland, from Ireland to Pennsylvania, from Pennsylvania to Carolina, from Carolina to the Mississippi Valley, from the Mississippi to Texas, from Texas to California, and from California to the rainbow’s end.

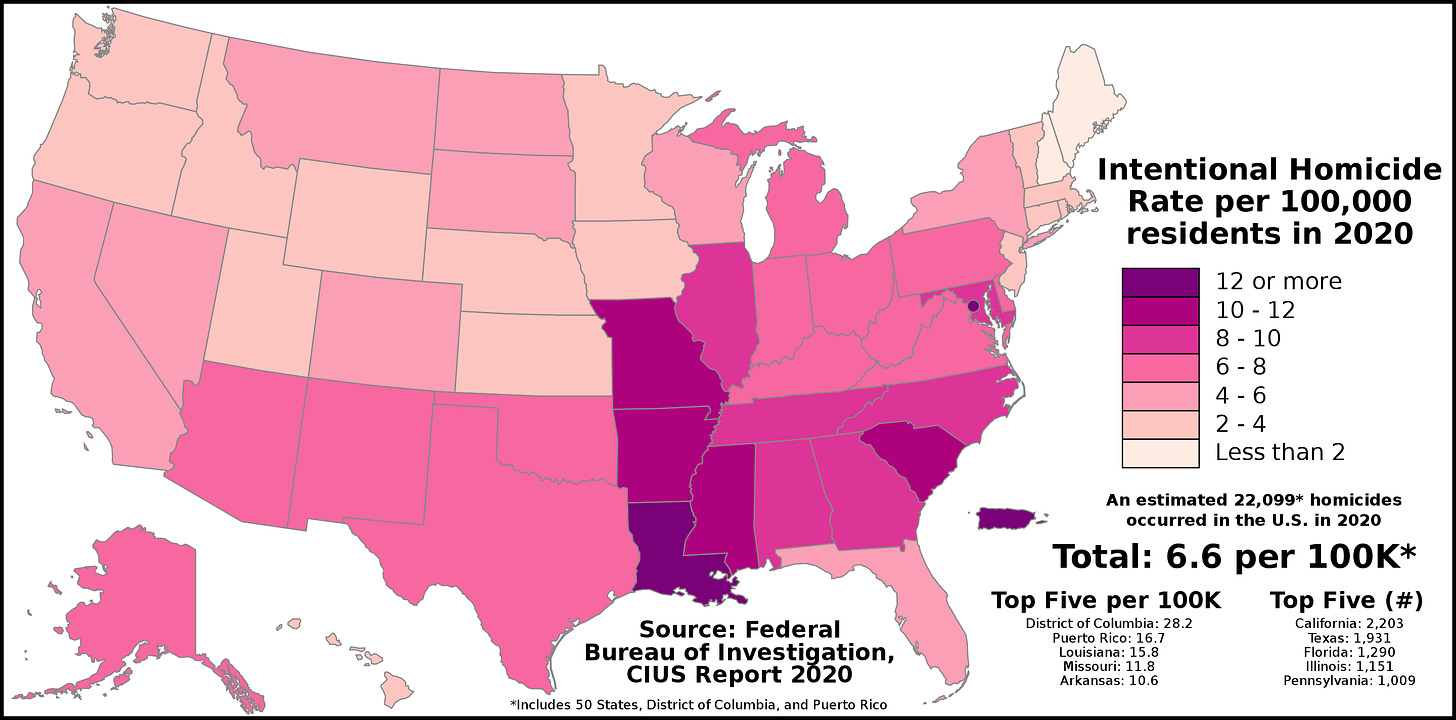

The Scotch-Irish “redneck” culture became a huge part of the culture of the South in general, but for present purposes, what was particularly determinative of the country’s future was the critical value it placed on personal honor and the need to back it up, when challenged, through physical violence. The continuity of this moral conviction is reflected in the distribution of violent crime in America today. In 2020, the states with the five highest rates of homicides per capita in the country included three states in the Appalachian backcountry and the old southwest: Louisiana, Missouri and Arkansas, as well as the quasi-Southern city of Washington DC. Four other Appalachian states and one adjacent southern state — Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama and South Carolina — were not far behind. The rate of violent crime in general was somewhat more spread out, but still distinctively clustered in the South, with the Appalachian states of Tennessee and Arkansas in the top five.

The national crime surge, of course, goes well beyond the South. The cities with the biggest increases in homicides between 2020 and 2021 were Chicago, Philadelphia, New York, Los Angeles, Houston, Baltimore, Detroit, Indianapolis, Washington DC and Dallas. But that only further evinces the persistence of the Scotch-Irish ethic of bellicosity: Aside from the few cities on that list that were already part of the Appalachian backcountry, every one of those cities lay along the path of the decades-long Great Migration of African-Americans out of the rural South and into the urban north, west and Midwest throughout the twentieth century.

The migratory path of Southern blacks became the next great line of transmission of Scotch-Irish culture to the farthest reaches of the continental United States, but this time carried forward by people whose ancestry did not trace back to the British Isles. Of course, American blacks had many more cultural influences than just that of the Scotch-Irish — most obviously the folkways of the African nations they hailed from, which is the subject of Fischer’s next book. But just as the Southern and Eastern European migrants who settled into the Northeast at the turn of the twentieth century absorbed and sustained the New England Puritanical culture that preceded their arrival, and as Hispanic Americans — both those who immigrated here and those who predated the British arrival — incorporated and reproduced the backcountry cowboy culture that was carried from the Appalachians to the vast region that we now call the Sun Belt with westward expansion, African slaves and their descendants were shaped in part by the North British culture of the region in which they were enslaved and imprisoned, and, in turn, brought it with them to the distant cities they escaped to.

In the very non-Appalachian metropolis I live in, as in many other American cities like it, this cultural legacy is clear as daylight in the distinct Southern drawl of working class African-Americans whose parents and grandparents migrated to the Bay Area from Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas. It’s just as apparent in that of working class whites, Asians and Latinos who have no genealogical connection to that region but who grew up in proximity to the children and grandchildren of the Great Migration. Those speech patterns, now known as “African-American Vernacular English,” followed the same cultural lines of transmission as the Scotch-Irish penchant for violent resolutions of conflicts. As Fischer points out, phrases like “he come in,” “she done finished,” “they growed up,” “he done did it,” and the words “man” for husband and “honey” as a term of endearment did not originate in the Southern backcountry, much less the American inner city, but were all in fact uttered in Northern Ireland and the English-Scottish borderlands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. “As early as 1772,” Fischer writes, “a newspaper advertisement reported a runaway African slave named Jack who was said to ‘speak the Scotch-Irish dialect.’”

If the accent and idiom of the Scotch-Irish migrants could be so readily absorbed by youth of myriad ethnic and geographical backgrounds who have never even stepped foot in that region, then why not the other cultural characteristics of that well-traveled heritage, including its heightened sense of personal honor, and its distinctive reverence — even if never acted upon — for the deployment of violence in defense of that honor?

This is what we have long known as “street culture,” or, less accurately, working class “black culture.” For generations it’s been associated principally with the concrete jungles of America’s biggest cities, but its origins were in the mountains of the rural south, and before that, the far flung provincial battlefields of the North British borderlands. The warrior ethic that presumed that, in the absence of a state monopoly on legitimate violence in the North British countryside, one’s physical safety could only be secured by demonstrating to others that an attack on one’s honor would assuredly be met with physical retaliation is the same one that, in the absence of a functioning law enforcement and criminal justice system in an American inner city, presumes that one can avoid being preyed on by others only by proving that you are not to be trifled with.

The provocative “mean mug” stare, the short fuse in the face of a perceived diss, the possessiveness over women when confronted by a male rival — these are all artifacts of the honor culture that found its way circuitously from the lowlands of Scotland and the northern counties of England to the streets of Chicago, L.A., New York — and Stockton, Española, and Florida City. By now it’s too ubiquitous to be associated with any particular ethnic group: for every poor black neighborhood in which looking at someone the wrong way could get you killed, there’s a poor white neighborhood somewhere with the same problem. Among the most dangerous cities in America are white Southern and Appalachian towns like Myrtle Beach (77 percent white), Louisville (70 percent white), Kansas City (61 percent white), South Charleston (82 percent white) and Martinsburg (80 percent white), West Virginia. We can call it “Scotch-Irish” culture, “Appalachian” culture, “black” culture or “street” culture, but at this point it’s probably fair to just call it American culture.

This is not the issue, but it is an issue to grapple with as we watch crime surge all around us. We can tell ourselves stories about how violent crime in the United States is merely a result of our depleted welfare state, or of some cultural pathology within “black culture.” Each is a comforting fable to its respective audience, allowing us to fit the problem neatly into our preconceived ideas of good guys versus bad guys and oppressors versus victims. But when a theory is too comfortable it usually means it’s too lazy. The more unsettling reality is that there’s something deep-seated within our national culture, that’s been a fundamental part of our value system from the earliest days of the new republic, that inclines us toward violence as a means of settling interpersonal disputes. That’s not the only thing that’s happening in our increasingly crime-ridden cities, but it’s one thing that’s happening. To ignore it is to continue to do what our political system does best: blaming our familiar enemies instead of regarding ourselves and each other as both part of the problem and part of the solution.

Subscribe to Social Studies

Politics, media and social theory

Another very thoughtful essay.

By chance I have Albion’s Seed on my To Be Read pile right now. I am intrigued by any discussion of the lingering effects of British culture on American life. I have long maintained the greatest legacy from the mother country, aside from the language of Keats, Milton and Shakespeare, is English Common Law. It is the latter, for example, that distinguishes the lands to the north and the south of the imaginary line we call the US-Mexican border, and is the primary reason thousands of people attempt to cross that border from the south every year, instead of the other way around.

Yes, I am a confirmed Anglophile, which doesn’t mean I am blind to the historical abuses and injustices of perfidious Albion; but that I also recognize the stunning cultural and legal gifts Britain has bestowed on the entire world, such as the notion that government power should be statutorily curbed to protect the rights of the individual (I believe the first Bill of Rights in history was the English one from 1689). Could there be any more succinct expression of the relations between the state and a free subject or citizen than that of William Pitt the Elder, 1st Earl of Chatham?

“The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the forces of the Crown. It may be frail — its roof may shake — the wind may blow through it — the storm may enter — the rain may enter — but the KING OF ENGLAND cannot enter — all his force dares not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement!”

(If he had still been Prime Minister during the Troubles between Britain and her North American colonies, there would not have been a Revolutionary War, IMHO)

ANYWAY, I was a very active gun rights advocate for about ten or fifteen years (until I gave up when I realized American gun owners were their own worst enemies on the subject: you can’t coherently defend the “right to keep and bear arms” when you don’t actually believe in civil rights). I spent a lot of time looking into homicide rates in different countries and US cities, and arrived at the conclusion long ago that these variances in “acceptable violence” are down to culture and have nothing to do with this or that law attempting to curb it. You reduce violence by getting to work on the culture behind it, and there is no wishing it away by banning this or that contributory behavior (as the utter failure of the War on Drugs makes crystal clear).

One thing that frustrated me was this notion that the US was a particularly violent society when compared to “other countries.” The “other countries” were always European countries (plus Japan and Canada) that had little in common with the historical development of the US. Better comparisons would be with countries that experienced, within generational memory, high levels of immigration; genocide of the indigenous population; civil war; the pushing forward of a wild frontier; and slavery. In short, most of the nations of the Western Hemisphere. And in that regard, the US looks pretty good (Canada looks even better). And again, I submit the essential difference between, say, the US (and Canada) and El Salvador is English Common Law, which among other things provides a moderating influence on inherently violent peoples . . . like the English, Irish and Scottish.

All cultures have their quirks, and compared to Continental Europeans, casual violence has always been more acceptable to Anglo-Saxons and Irish. I lived in the UK for a couple years and saw this first-hand: you are much more likely to get into a bar fight in the UK, if you aren’t careful, than in most of the US, and certainly Continental Europe (I believe this is because Europeans are simply less violent; while American behavior is probably moderated by the very good chance your bar antagonist might be armed). When I returned to the US from the UK and spent a lot of time in Irish bars (which attract British expats as well as Irish and Irish-Americans), I saw much more fighting in the latter than in other bars, partly because most Americans would never expect the sort of escalation that can happen if you casually insult or irritate a drunk Brit or Irishman.

Another fun fact I used to deploy in my criticisms of gun controls: the homicide rate in Britain is (handwaving a little here) four times that of Germany, though both countries have very similar laws regarding weapon ownership. So how do you account for that? Culture. The laws mean nothing.

When you look at the supposedly extremely violent “Old West,” you find that most of the senseless violence between white people was not so much among cowboys of movie legend, but along the railroads, which were built with Irish labor (except for the Central Pacific, which used Chinese). The casual violence and murder was really unbelievable in the mobile labor camps called “Hell on Wheels.”

So what happened to these ultra-violent Scotch-Irish? Somehow, over a period of decades, they were integrated into the broader, less violent American society (there were times and places in US history when it wasn’t even against the law to dispatch a pesky Irishman, so reviled were they). Indeed, by the turn of the 20th century many police forces of large eastern cities were largely Irish-American. It took time.

It’s okay talking about violent Scotch-Irish culture, but for some reason you can’t go there when we have a similar terrible problem in our inner cities. There are two interviews with former Chicago mayor Rahm Emmanuel I’ve seen on YouTube, one early in his, um, reign, and one apparently conducted after he’d already decided not to run again. In both interviews the same question was asked: “Why is there so much killing going on in Chicago?” In the first interview he blamed the (lack of) gun control laws in Indiana (of course the next question out of the mouth of any thoughtful journalist would be, “So how come Indiana doesn’t have anything like Chicago’s level of violence?” but that didn’t happen). Good old Rahm Emmanuel, keeping on message.

In the second interview, he answered the question differently: he suggested (I’m paraphrasing) the culture was broken and needed to be fixed. For this comment he was roundly attacked by the media.

This year Lori Lightfoot was asked the same thing and not only did she blame Indiana, but Michigan and Wisconsin as well. And anyone who disagreed with her was a racist, misogynist and homophobe, so there, case closed. This is a woman who literally does not care how many citizens of her city are murdered every year. But I digress . . .

I have referred to it as “urban black culture” in the past because I couldn’t imagine anyone was stupid enough to believe I or anyone else was suggesting there was a genetic, racial component to it, but as you suggest, there are indeed people that stupid, and lots of them. So referring to it as “street culture” makes a lot more sense (who cares what race the people involved are? I don’t), though that will probably get you attacked for “using white supremacist code.” And are there Scotch-Irish roots to it? Why not? You make a good case. And if any indigenous West African culture remains among urban African-Americans (I doubt it, but anthropologists say some does), well, that’s a part of the world with pretty eye-watering casual violence too.

The late George Macdonald Fraser, in one of his Flashman books, referred to the Scots as “Britain’s own home-grown savages.” He ought to have known; he was of Scottish background himself and was a junior officer in a Highland regiment following the war. He also wrote a book, The Steel Bonnets, about the Scottish Borderlands (which is also on my TBR pile). I recently completed his memoirs of his wartime and postwar military life, and long ago eagerly consumed all his Flashman stories. You might want to check him out.

Sent your book recommend to my grandson in Japan (teaching ESL) and just got this reply: "I just finished reading American Nations by Colin Woodard. Its also about how different settlement patterns continue to influence modern American politics. He mentions Albion's Seed a few times as an influence. It was a very interesting read, I recommend." More to read!