On the night of the Fourth of July, amidst a scene of chaos in San Francisco’s Mission District, a mob of revelers lit a bonfire in the street that quickly grew large enough to threaten nearby buildings. The police were dispatched to the scene, where they faced a hostile crowd. The SFPD claims that 12 officers were injured from people shooting fireworks and lobbing glass bottles at them. This is how my friend and colleague, the reporter Lee Fang, described what he watched from the roof of his building:

The San Francisco police assembled and waited for over an hour while the 24th and Harrison bonfire grew and crowds began attacking a MUNI bus. At one point a speeding car almost ran through the column of cops while they dithered several blocks away. The car taunted the officers and fled. The restraint verged on the absurd.

There was no clear purpose to the crowd’s violence. There was no big looming social grievance. It wasn’t a political demonstration. It wasn’t even a premeditated riot like Portland saw that same night (and on many, many other nights besides). By all indications it was just spontaneous, pointless, drunken mob chaos, reminiscent of what we’ve grown used to seeing every time some city’s home team wins a championship.

There have been a lot of words written about the mayhem that has consumed San Francisco in recent years. I’ve written a few of them myself. It’s true, though, that in most of the city, on any given day, things look pretty normal. You can still go pick up a cappuccino and a croissant at Tartine on a Sunday morning and walk up to Dolores Park to people watch, without seeing a single street addict smoking meth along the way. You can drive out to Land’s End for a hike to the beach, and when you get back your car windows will probably still be intact. The dystopian social decay that’s so ostentatious in the Tenderloin and SoMa is barely visible in Noe Valley and Pacific Heights, and even in the Mission it’s mostly in your peripheral vision.

But that doesn’t mean it’s contained. The second order effects of downtown San Francisco’s lawlessness are everywhere, even if you can’t see them. And this is why I believe that the consequences of the anarchy the city allows to persist downtown are, if anything, understated.

Political progressives tend to approach criminal justice with blinders on. In the American cultural tradition of staunch individualism, and in the Enlightenment intellectual tradition of instrumental rationalism, they typically regard it as nothing more than a set of tools the state uses to control individual behavior. The purposes of our criminal codes, they argue, are threefold. First, they enforce lawful conduct by demonstrating to would-be perpetrators that should they engage in a criminal act, they can count on being punished harshly (deterrence). Second, they take criminals off the street, denying them the opportunity to commit more crimes (incapacitation). Third, they inflict revenge upon wrongdoers (retribution). Typically, progressives express ambivalence about the first two aims, and outright opposition to the third.

But if you shift away from the individualist-rationalist vantage point, as Emile Durkheim did in his book The Division of Labor in Society, the inverse case comes into focus: Social vengeance is, in fact, the most critical function of our criminal justice system. And if you stand for the principles the political left purports to defend — fairness, peace, and social solidarity — then you should prize it above all else.

As social policy, deterrence has always been of empirically questionable value. Likewise, the practical limitations of a strategy based on incapacitation, to say nothing of its moral shortcomings, was shown plainly by the failure of the War on Drugs. Both are weak intellectual foundations upon which to build a massive coercive state apparatus. Revenge, however, serves a fundamental social purpose, without which you really can’t have a social order at all.

Durkheim argued that crimes represent injuries not just to individual victims but to society as a whole. This sets them apart from mere civil violations, like a breach of contract. If you break a contract with your neighbor, he can sue you. If you lose, you’ll be forced to pay him restitution. You won’t go to prison, and you won’t be forced to pay a fine to the state to make symbolic amends with society at large. You’ve made the injured party whole again, and that’s considered a just resolution of the infraction.

But if you maim your neighbor, you’ll be charged with a felony crime on behalf of the entire society. Your case will be titled “The People Versus —,” or “The United States Versus —,” not “Mr. Johnson Versus —.” If you’re found guilty, you won’t just be forced to compensate your neighbor for his medical bills and for future earnings lost as a result of his injuries. You’ll go to prison, probably for a long time. This will happen even if your neighbor forgives you and objects to your being punished. It’s not up to him. A crime is not just the prerogative of the victim; it’s everyone’s business, because a crime is an offense against the entire society and everyone within it.

It’s not that your fellow citizens suffered any particular material harm by your crime, it’s that you violated a moral principle that everyone has a stake in. That’s what sets it apart from a civil lawsuit. We may not all agree that your contract with your neighbor was fair; some of us may not believe in the sanctity of contracts at all. No moral consensus is threatened by your breach of it; it’s a private matter between you and him and the judge as the arbitrator between you. We all, however, believe that it’s wrong to maim other people. By violating that moral principle, you have ruptured that consensus: you have shown yourself to be someone who does not, in fact, share that moral belief.

By punishing you, we repair that break. We show the public that the consensus still holds, and that those who stand outside of it will pay a price. The punishment establishes the violation as an exception, rather than as a new norm. This is one reason why showing remorse is such an important part of sentencing: by doing so, the violator helps to restore the authority of the moral rule he has undermined through his transgression. Conversely, the remorseless suffer harsher punishments because there is that much more of a rupture with the moral consensus to compensate for. And without that moral consensus, we cease to have a functional social order. Punishment, Durkheim writes, “is above all intended to have its effect upon honest people.” It coheres individuals into a moral community.

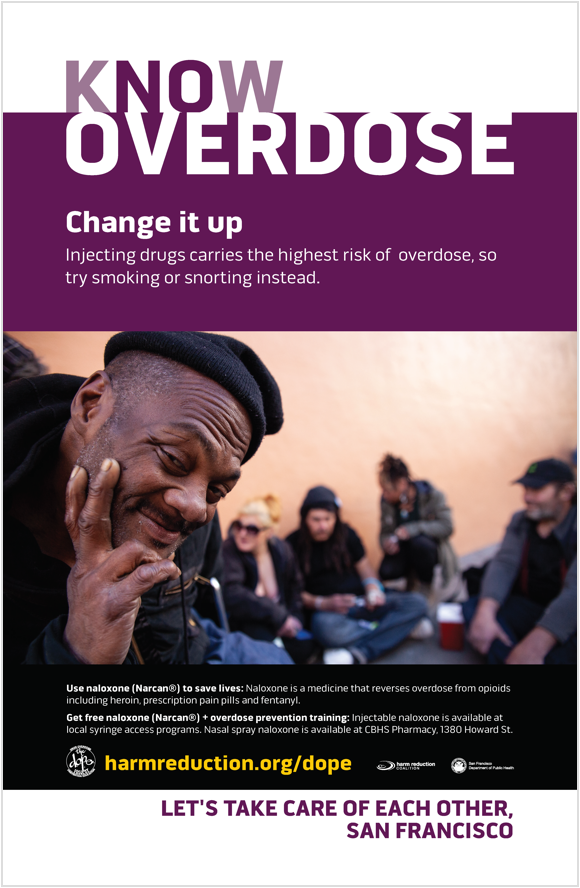

When you remove punishment from the criminal justice process, those norms, when violated, are never restored, and the moral consensus erodes with each unpunished transgression. The social fabric frays. This is the long term cost of a policy of impunity, which is what reigns in San Francisco when it comes to drug use, drug dealing and the petty property crimes that fuel drug consumption. Along with non-enforcement has come, inevitably, destigmatization, which is the express goal of the “Harm Reduction” advocacy groups that hold so much power over public policy in the city.

I could expound on why I believe destigmatization of drug use and drug dealing is a disastrous idea (I’ve already done so for legalization), but for present purposes it’s beside the point. More important is that the legal purgatory that San Francisco’s political leaders have created downtown is a catalyst for social destabilization throughout the city, and maybe throughout the region. It’s no hyperbole to describe the present condition in San Francisco as one of contested sovereignty. In much of the city, normalcy endures, while in the Tenderloin and parts of SoMa, one could say it’s become unclear exactly who’s in charge, but that’s not actually true: it’s plain to everyone that the drug dealers are. It’s insane to imagine that such a situation could persist without fundamentally subverting the social order. It has already obliterated the legitimacy of the city government’s authority (hence the Chesa Boudin recall), but, I suspect, it has also had an even more profound effect: it is undermining the legitimacy of law and order itself, and with it, whatever sense of community remains in the city.

Of course, some on the cosplaying left will celebrate such an eventuality, the very idea of “law and order” implying, to them, authoritarian rule. These are not serious people. As Durkheim has taught us, our penal codes are not some diktat imposed on us by an alien regime or an oppressive ruling class. They are the pre-conditions of our collective existence as a community with common values and shared moral principles — in other words, of society itself. In their absence is found not emancipation but barren individualism, atomization and nihilism. We are beginning to see the outlines of that world already.

Portland terrorists (aka "antifas") will use ANY reason to riot.

The most recent excuse was the ill-advised SCOTUS decision on abortion that I would estimate 80% of my fellow Oregonians disagree with.

So, why are they rioting? Have women been forced to look to back alley abortionists?

No. In fact Oregon is building clinics to allow women from nearby Mountain states that are likely to "trigger" abortion prohibitions in those states.

Oregon not only has zero barriers to abortion, something I and many Oregonians agree with, but there are no barriers because of age, residency or income. In fact Oregon's State Constitution guarantees a woman's right to choice, so that absent an actual federal ban on states allowing abortion (something that exists only in the fevered imagination of radicals and Clarence Thomas) there is literally no place IN THE WORLD that makes access to abortion easier than Oregon.

So, why are they breaking windows, setting fires, and violating the law while police stand by and "observe?" Because they like burning and destroying stuff and spreading terror in a once-weird but cool community.

I was born and raised in the Bay Area and lived in San Francisco for thirty years. I moved out of state a year ago. I have children and I was very concerned for their well being and safety as they moved into adolescence. It broke my heart to leave the city that was once my home. I left behind a community of cherished friends and colleagues. I hold precious memories from my childhood to adulthood. Dinner celebrations at the Cliff House. Restaurants from North Beach to the theatre district where I’d waited tables as I worked to make ends meet while pursuing creative endeavors. Meeting my husband in the theatre. Getting married at City Hall. The birth of my own children and the years dedicated to their school and our church community. My volunteer work with a number of organizations. All in San Francisco. Sadly, I also witnessed it’s demise. I remember my then 7-year old son asking me why the man on the corner was giving himself “a shot”. Being chased by a meth head with my other son on our way home from the park on a Sunday afternoon. Walking over bodies to get to my front door with my children in tow. After personally witnessing two flash mobs raid my local Walgreens, I no longer allowed my children to come with me when they simply wanted to tag along to look in the toy section. I could no longer rationalize staying in San Francisco with the hope that things would improve. When I finally left, I didn’t move. I fled. I am homesick everyday, but the city I once loved is gone.